Cesare Casella and I both moved to New York in 1993 - and eventually, oddly, his family and mine ended up living in the same apartment building. By then I had long admired the food Cesare served at his various restaurants - Beppe, Maremma, Salumeria Rossi - and I followed him from one to the other.

But eventually he had no more restaurants, and one day when I ran into him in the lobby I asked what he’d been up to.

And then I wrote this story.

You’ve probably never heard of him, but in the world of restaurants few chefs are more beloved than Cesare Casella, a big-hearted Tuscan who strolls through the world with a smile on his face and a sprig of rosemary in his pocket. “Cesare knows everyone, he knows everything about food and he’s the most generous guy in the world,” says meat master Patrick Martins. “When we had the pig catastrophe he was the first person I called. I figured if anyone would know what to do, it would be him.”

Martins runs the country’s major supplier of ethically raised meats, Heritage Foods USA, and in early 2016, when the Edwards Virginia Smokehouse burned to the ground, he was distraught. He knew this spelled disaster not only for the Edwards family, which had been curing hams for ninety years, but also the farmers who raised the ancient breeds they required. Unlike commodity pork, bred in factory farms to grow fat fast, the Edwards’ relied on pastured pigs raised as they’ve been since the beginning of time. “You can’t make traditional ham with commodity meat,” says Martins, “after a few months it just turns to dust. You need good genetics, and one of our Missouri farms has Berkshire pigs with genetics going back to Oliver Cromwell. Raising pigs like that takes time, and our farmers had a year’s worth of pigs in the ground. The Edwards’ were using 250 legs a week, and if I couldn’t find a buyer for them, the farmers were going to go broke.”

Cure-masters throughout the south agreed to take the current crop but it was a temporary reprieve; Martins worried about the following week – and all the weeks to come. “To my surprise,” he says, “Cesare said, ‘I’ll take them all. I’m going to start making prosciutto.’ And all I could say was, ‘Are you sure?’”

Curing ham the old-fashioned way requires an enormous commitment of time and money; traditional American ham is made from nothing more than pork, salt, smoke and time. Classic Italian prosciutto is even simpler: the hind legs of pigs are rubbed with salt and allowed to hang, in a temperature-controlled atmosphere, for a minimum of 400 days. “It was a challenge,” admits Casella, his Italian accent still strong after twenty-five years in America. “But I decided to put everything I had into the venture.”

Casella was not unfamiliar with pigs. He grew up in the hills outside Lucca, where his family raised their own chickens, vegetables and herbs for their restaurant, Vipore. They also raised a few pigs to make the restaurant’s sausage, salami and prosciutto. “American pigs taste different than the ones we raise in Italy,” he says, “but I knew those were happy animals that had good lives, and I thought if I took enough time and aged on the bone, I could make great American prosciutto. I’d just sold my restaurant, Salumeria Rossi, so I thought, why not? I’ll take the risk.”

Nobody who knew Casella was surprised. In 1992, after earning a Michelin star for the family restaurant, Casella arrived in New York and started looking for ways to translate his native cuisine to his adopted home. He began with beans.

Tuscans eat a lot of beans, but Casella didn’t think much of the ones he found here. So he persuaded a farmer he met at the Union Square Market, Rick Bishop, to grow nineteen different varieties just for him.

Then he turned to beef. He was determined that his first restaurant, Beppe, would serve classic bistecca alla Fiorentina, which relies on the meat of the beautiful white Chianina cattle of Tuscany. There was none on the market, but Casella was not daunted. “They wouldn’t let me bring cows from Italy, so I bought some Chianini from a farm in Texas and started raising them in upstate New York.”

“I heard about this crazy guy who named his cows after Puccini operas,” says Patrick H. Dollard, the only other Chianina breeder in the state, “and I knew I had to meet him. So I went to Beppe… and it changed my life.”

Dollard is neither cattleman nor farmer: he is the President and CEO of The Center for Discovery, a care facility for people with developmental disabilities in the foothills of the Catskills. His cows were part of a radical approach to integrating nutrition and illness. “When I first came here, more than thirty years ago,” he says, “I had the stench of institutional food in my nostrils. Our kids are medically fragile, but they’re capable of getting well, and I wanted to blow the system up and get them good food.” One look at the bucolic campus makes it abundantly clear that this is not a man who’s content with half-measures; the dozens of buildings – clinics, barns, houses, schools, greenhouses and bakeries – he’s built in the ever-expanding Discovery Center sprawl across 300 acres. About half of that is an organic, biodynamic farm.

This is a place where wheel chairs roll into the fields and blind people ride horses, a place so inspiring that it’s easy to understand how Casella felt on his first visit. “I came to see Patrick’s cows and it was like finding a little piece of Tuscany. It all felt so familiar; the animals, the fields and the people were all part of the life. And everyone was so nice! I thought - caring for the disabled like this? I never saw that before. But I thought it was cool.”

“We began talking,” says Dollard, “and we never stopped. I soon realized that Chezzy isn’t just a chef. He’s a great agronomist. He’s a scientist. He’s a ….” He stops, uncharacteristically lost for words. Drawn by the atmosphere and intrigued by the mission of using food as medicine, Casella began showing up at the Center in his spare time. “Being there,” he says, “just made me feel good,”

The visits gradually turned into a working relationship and Casella began reorganizing the way the system worked. “Before Chezzy came, “says Dollard, “we had farmers, we had nutritionists and we had cooks. But they didn’t talk to each other. All that changed in 2012 when he agreed to become Chief of the Department of Nourishment Arts.” Casella’s staff – some fifty farmers, chefs, bakers and nutritionists - feed not only the thousand people living at the center, but also the 1500 people who care for them. They have their own bakery, their own herb shop, their own CSA, even their own market in the tiny town of Hurleyville selling the farm’s culinary herbs, herbal teas, vinegar, pickles, honey, and cereal.

It’s an enormous job, but as Casella strolls through the fields, he makes it all look easy. He pulls some green garlic from the ground and sniffs appreciatively at the aroma now filling the air. He says hello to the 1200 laying hens, and goes looking for the pigs who have retreated to a sheltered spot beneath the trees. He points to a huge hoop house filled with basil; “We’ll freeze most of this for winter.” Then he wades in among the tomatoes, brushing against the fragrant leaves, seeking out the ripest ones. “These were the first canestrino di Lucca tomatoes in America,” he says, gently stroking the strangely ribbed orbs. “When I couldn’t find them here I planted seeds from home; they make the best sauce.”

When the Hudson Valley Seed Company got wind of these unusual tomatoes, they wanted to sell the seeds. “They named them for me!” Casella says as if he can’t imagine why they’ve bestowed this honor upon him. But as I watch him tenderly touching each tomato I understand his prosciutto dreams. He may have left Italy, but like the accent he’s never tried to lose, he carries it with him wherever he goes.

“He hovers over those legs,” says Martins, “anxiously watching them. He wants them to be perfect. Last spring, when the first prociutto was finally ready, he was so nervous. He went around asking what everyone thought. Was it good enough?”

Softer than the prosciutto of Parma, the color a paler pink, Casella’s prosciutto has a deep rich flavor and a lacy edge of creamy fat. It was an instant hit with chefs. Alice Waters, of Chez Panisse, was one of the first customers. So was Andrew Carmellini of Locanda Verde. Today Casella prosciutto is on menus all across the country. And although Casella now has 7,000 heritage pork legs slowly turning into prosciutto, Martins worries that it won’t be enough. “Everyone wants it,” he sighs, “and I’m anticipating a prosciutto shortage.”

Casella shrugs. He’s on to his next project. “I’m thinking,” he says, looking off into the fields, “of…..” He stops, and I wonder what it will be. Something new. Something Italian. And something very delicious.

And now we know what that something is.

Cesare’s latest obsession is vinegar, which he is making using a sixteenth century Tuscan method at his Acetaia del Sole. You can buy this remarkable apple cider vinegar from Heritage Foods. Aged in whiskey barrels, it has far more complexity than ordinary cider vinegars.

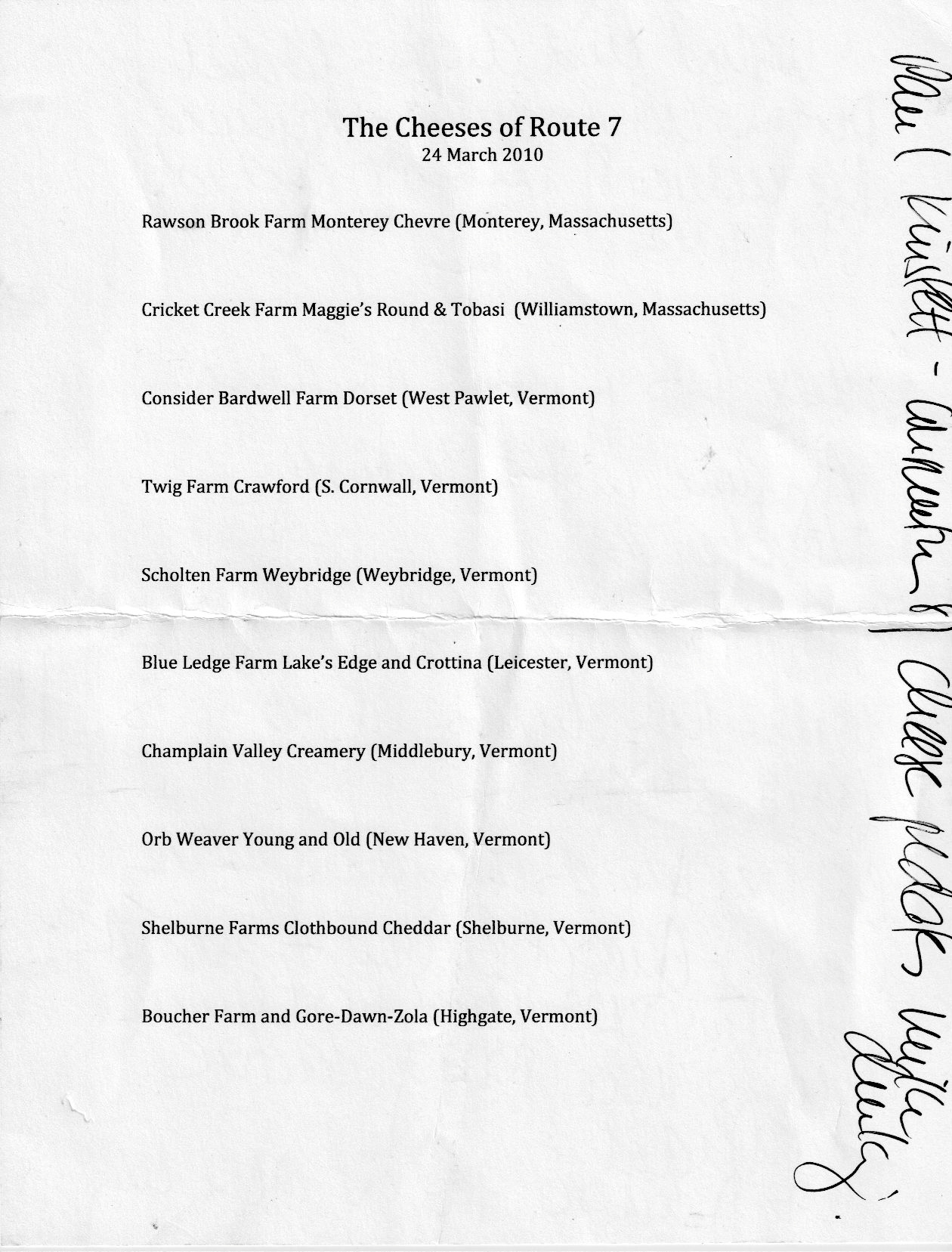

Since we’re in the Hudson Valley…. One of the nicest things about living here is that we are rich in great cheese makers, and great cheese stores. Rubiner’s, in Great Barrington, is truly world class. Matt Rubiner offers occasional cheese classes, and about 15 years ago he decided to investigate the cheeses made along a single rural road.

I hope he’ll do it again; I learned so much.

(And if you’re curious about the illegible scribble I made on the side, here’s a translation.“Paul Kindstett (a recently retired professor of food sciences at the University of Vermont who has written extensively about the history of cheese) says that the consumption of cheese predates milk drinking”.)

Speaking of Tuscany….People tend to go a little crazy over the fried artichokes at I Sodi. I like them too - who wouldn’t? They taste like potato chips with a college education, and it’s hard to think of a more seductive fried food.

Bur for my money it’s this lemon pasta - understated, tangy, with that adorable little smattering of pepper across the top - that’s the dish to die for.

While I can’t offer you the I Sodi recipe for lemon pasta, here’s one I learned from the late actor Danny Kaye who was, truly, one of the best cooks I’ve ever been lucky enough to know.

Lemon Pasta

1/2 stick (1/4 cup) unsalted butter

1 cup heavy cream

3 tablespoons fresh lemon juice

1 pound fresh egg fettuccine

2 teaspoons fresh lemon zest

salt

freshly ground pepper

freshly grated Parmesan cheese

Melt butter in a deep heavy 12 inch skillet and stir in the cream and lemon juice. Remove the skillet from the heat and keep it warm and covered.

Cook the pasta in a large pot of salted boiling water until al dente.

Reserve 1/2 cup of the pasta cooking liquid and drain the pasta into a colander.

Add the pasta to the skillet with lemon zest and 2 tablespoons of the pasta cooking liquid and toss well. (Add more pasta cooking liquid, 1 tablespoon at a time, if necessary to thin sauce.)

Season the pasta with salt and pepper and serve with Parmesan cheese.

Beautiful and inspiring on every level. Can't wait to try the lemon pasta!

What a great story. I might have to buy some apple cider vinegar. But the story about The Center for Discovery really moved me as I have a daughter on the severe end of the autism spectrum and would love for her to be at a place like this. Always nice to be reminded of all the good people doing good things.