Ode to A Great Chef

A memorable meal at Jamin. A lost chapter from The Paris Novel. The world's best mashed potatoes. And a kitchen tool I love.

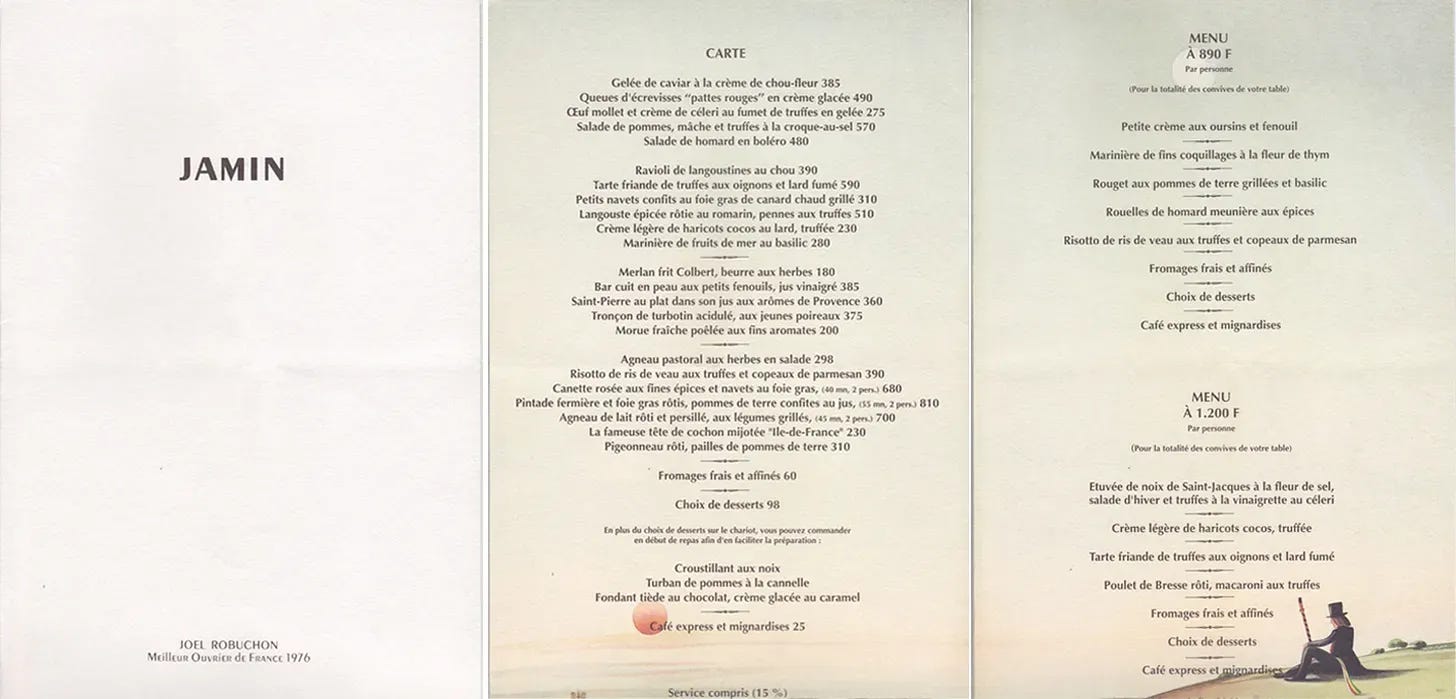

Some meals are so shockingly good that the memory lingers for the rest of your life. That was my first experience of Jamin, the restaurant Joel Robuchon opened in Paris in 1981.

I went in 1983, when Joel Robuchon had only one Michelin star (he got his second star that year). But with my very first bite I knew I was in the hands of a master. It was such a memorable meal that after all these years I can still taste that amazing caviar gelée with cauliflower cream.

I tried to write about that meal in The Paris Novel, but in the end I gave up: the food had became too dominant. But here’s a little snippet that landed on the cutting room floor. The person speaking is Jules.

“I want to tell you a bit about the chef. Joel Robuchon is young, but I think he is going to be very famous. He is trying to change culinary history, abandoning the past to cook for the way we live today. He is attempting to pare the food down, make it far less heavy. I am eager to see what you think.”

The chef immediately spotted Jules, and the chubby face beneath the tall white toque broke into a grin so wide it reminded Stella of a cherub in a medieval painting. He greeted them, led them to a table and signaled for a waiter. A bottle of Chablis appeared and they sipped it as the two men solemnly discussed the menu.

While they talked Stella looked around the room. It was small and slightly fussy, stuffed with mirrors, a small chandelier, wall sconces, framed prints…. She had the not very charitable thought that the chef should try paring down the decor along with the menu.

When the chef had gone Jules said, “Yes, I agree. Decor is not Joel’s strong suit. But I think you will find that the food is everything this room is not.”

“For your first course,” he waiter intoned the words with obvious pride, “I offer you soupe chaude a la gelee de poule.” His voice promised a world of wonders hidden in the tiny vessel he set before them. “Straight down.” He made a scooping gesture with a spoon. Stella did as she was told, closed her eyes and let out a little moan.

A savory cloud of custard trembled above a puddle of nearly liquid foie gras. Jules watched her abandon herself to the sensations, eating with her eyes closed, and thought, once again, that she ate as if she heard music. He wished for a camera: her pleasure in the food transformed her face. Even with her eyes closed, it had an open, vulnerable quality.

At last she opened her eyes. She looked down at her empty bowl, as if searching for a morsel that might have escaped. Jules silently handed his own unfinished bowl across the table. “You sure?” she asked as she accepted it.

When the waiter arrived with the second course he was carrying two small plates. “Etuvée de noix de St. Jacques au fumet de champignons.” The words were as portentous as if he were announcing the arrival of the Queen of England, and Stella was disappointed to look down at nothing more than a few white circles in a pale froth. “Scallops,” murmured Jules, “in a concentrated mushroom broth.”

Stella touched one of the circles with her spoon and it began to shiver. She put it in her mouth: smooth, silken, barely resistant to the teeth, it hinted at the sea. She spooned up some liquid and her mouth was flooded with an earthy forest taste. She took another bite, and then another, forgetting where she was, simply following the flavors in her mind.

“Amazing, isn’t it?” She opened her eyes to find Jules staring at her. “It takes a true artist to make something so simple become so complex.”

“Like your bird,” she said.

His smile was enormous. He lifted his chin a bit directing her attention to another table where a young Japanese woman was eating fiercely, with great concentration. Beautifully dressed in a simple black silk suit she was conspicuously alone in this room filled with couples.

“Like a guest to herself,” she whispered.

Robuchon was a great chef, but he might be most famous for his potatoes. These are special because the chef took advantage of the spud’s ability to absorb an extraordinary amount of butter: a pound for every two pounds of potatoes. (Being a reasonable person, you probably balk at all that butter, but you owe it to yourself to try this at least once.)

A few notes on potatoes. They are divided into baking potatoes, like russets, and boiling potatoes like Yukon Golds. Bakers fall apart more easily, which means they will absorb more liquid and give you fluffier results. You get creamier results with boilers, but you have to work considerably harder. Robuchon preferred a kind of boiler called ratte, although you could easily substitute fingerlings or Yukon Golds.

Your mashing utensil is equally important because they release the starch in potatoes in different ways. An old-fashioned potato masher has the advantage of allowing you to mash the potatoes right in the pot, but it will always leave a few lumps (there’s nothing wrong with that). A ricer will give you lighter, fluffier potatoes - and it’s easier to use. You can achieve the smoothest, creamiest results with a sieve, but your arm will hurt. Beware an electric mixer, which will release too much starch and make your potatoes gluey. And never allow a food processor to come anywhere near your mashed potatoes: you’ll end up with a fairly disgusting substance that is somewhere between library paste and glue.

A few more helpful hints on mashed potatoes: Do not overcook your potatoes or you will end up with a watery mash.

Return your potatoes to the empty pot for a few minutes after they are cooked and drained. This will remove as much water as possible, giving you a more satisfying texture.

Warm whatever liquid you will be beating into your potatoes. If the liquid and the potatoes are at the same temperature, they will slide more easily together.

Robuchon Potatoes

2 pounds boiling potatoes, such as Yukon Gold, fingerlings or ratte

1 pound unsalted butter, chilled and cut into cubes

1/4 - 1 cup milk

Boil the potatoes in well-salted water for 18 minutes.

Drain the potatoes and quickly peel them. (The chef considered peeling the hot potatoes the most difficult part of the recipe.)

Put the now empty potato pot back on the stove over low heat.

Heat the milk in a small pot until almost boiling; Robuchon insisted that the milk should be tres chaud.

Sieve the drained potatoes into the pot and stir them, over the heat, with a rubber spatula or wooden spoon until they are very dry. Still stirring vigorously, work the cold butter, pat by pat, into the potatoes. Keep stirring; this one is hard work.

When the mixture is very creamy, slowly add the hot milk until you achieve the consistency you want, and season to taste with salt. At this point Robuchon put the potatoes through yet another, finer sieve. But I’ve always skipped that step.

Serve to 6 lucky people.

I’ve spent a long time searching for the perfect salt receptacle to set next to my stove, and I think I’ve finally found it. The Zero Japan salt box is large enough to hold a lot of salt, and the cypress lid is easy to open with one hand. It has a convenient handle. It comes in a lot of colors. And it looks quite handsome sitting on your counter.

The solo, young, elegant Japanese woman at Reblochon so absorbed in her eating…I may have seen her at Chez Allard in the early 90’s. I was there with two colleagues having a wonderful slow lunch. A young, solo Japanese woman sat down to eat. An entire bowl of salade de haricots, a whole canard aux olives. And more. We were quite overcome at her prodigious appetite and concentration. Oh, I long to go back.

Love the phrase “like a guest to herself”! Thank you for another way to more fully appreciate experiences on my own.