Who Are the Ten Most Important People in the History of Food?

Also, a very ambitious vintage menu for New Year's Day. And one of my favorite recipes for children.

A few years ago a publication asked me to answer an intriguing question: Name the ten most important people in the history of food.

I struggled with my answers for a few days, and kept changing my mind. The first person I thought of was Christopher Columbus, who completely changed the way the world eats. Before his voyage there were no horses, pigs or cows on the American continent. He also took a whole slew of plants to Europe from whence they traveled to Africa and Asia. Without Columbus there would be no tomatoes in Italy, no chiles in Thailand, no peanuts in Africa or potatoes in Ireland. And that’s just for starters.

But before Columbus there was Alexander the Great, whose tutor Aristotle encouraged him to take botanists along on his journeys of conquest. In the third century, BCE, he changed Greek society by bringing citrus, peaches, pistachios and peacocks into the country for the first time.

In between, of course, there was Marco Polo. He may not have brought noodles back from Asia, but he returned with many other foodstuffs.

Then there are the cookbook writers. Careme, Escoffier. The English Robert Mays, who wrote a much-read English cookbook in 1588. The author of the extremely influential Le Cuisiner Francois, which disseminated the principles of French cooking in 1651 and was widely translated into other languages. (It was in print, in English, for more than 200 years.) And of course the great Chinese scholar of the Ch’ing Dynasty, Yuan Mei.

What if we concentrate only on America? Even so, it’s hard to narrow the list down. It probably would have to start with Thomas Jefferson, who was responsible for bringing us so much of what we eat today. He even tried planting olive trees in Virginia. “The olive," he wrote, "is a tree least known in America, and yet the most worthy of being known. Of all the gifts of heaven to man, it is next to the most precious, if it be not the most precious. Perhaps it may claim a preference even to bread; because there is such an infinitude of vegetables which it renders a proper and comfortable nourishment.” (Jefferson may have been the Michael Pollan of his time; he was a great believer in eating vegetables.)

It’s kind of an impossible question. In the end the list concentrated most heavily on famous chefs (Julia Child), and contemporary influencers. But it pains me that the great Angelo Pellegrini, who pretty much invented Slow Food 60 years before its time (and also published the first recipe for pesto in America), will be forgotten. And what about Fannie Farmer, who made cooking “scientific”? Or Chuck Williams, who brought us most of the tools we now consider necessary, thus reinventing the way we cook? (I wrote about him here.)

Thinking about this has been a lot of fun. Who’s on your list?

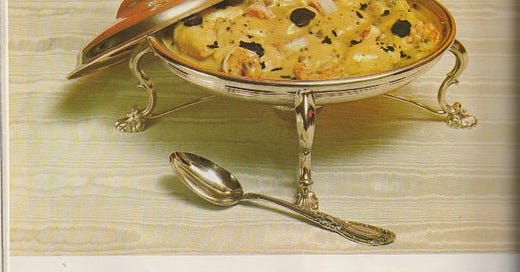

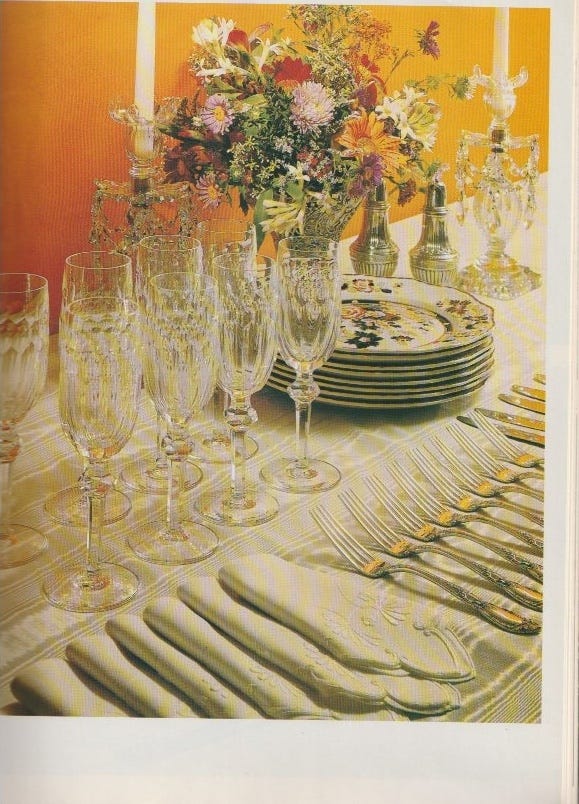

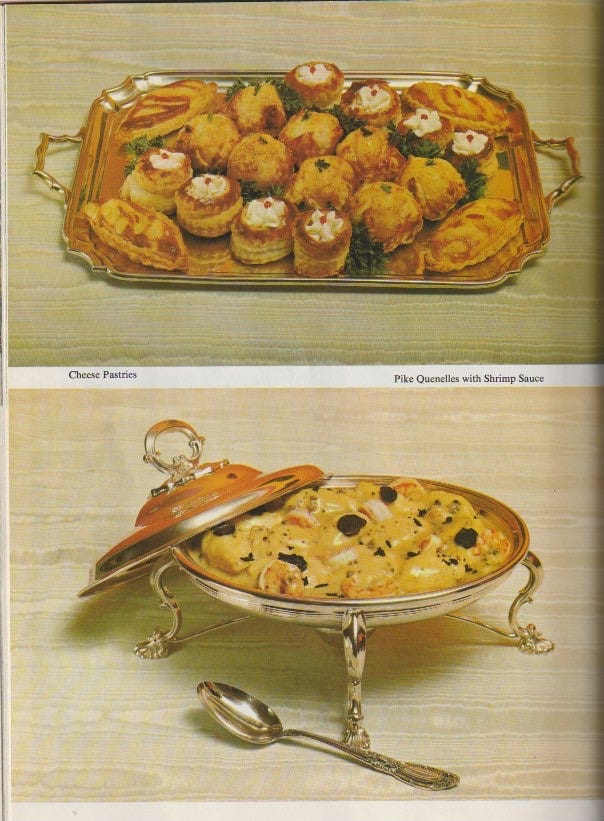

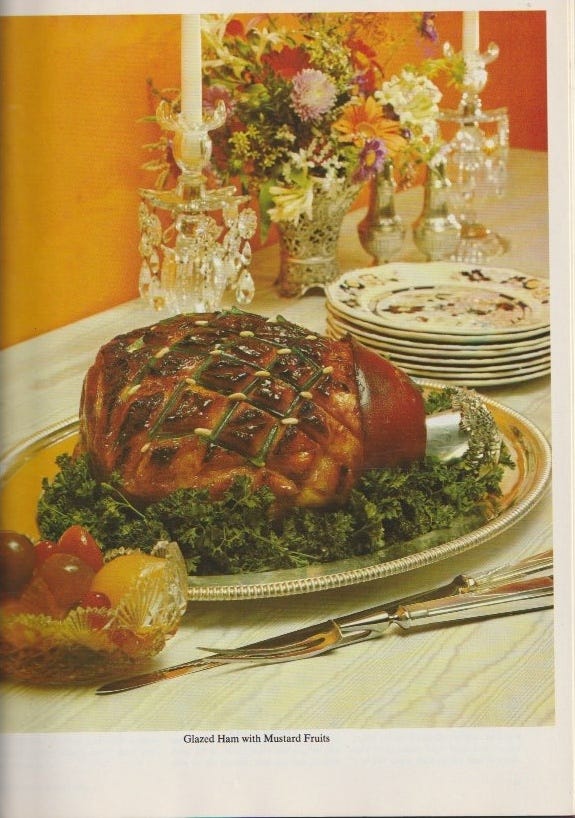

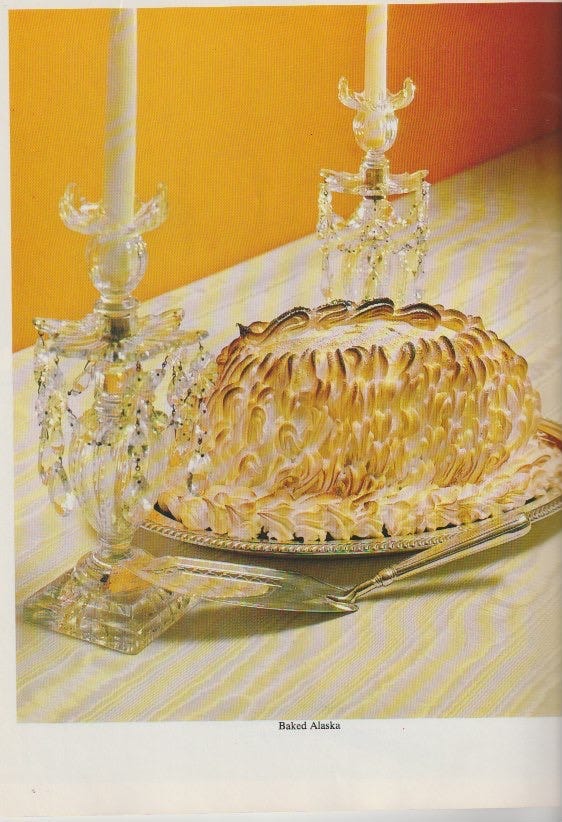

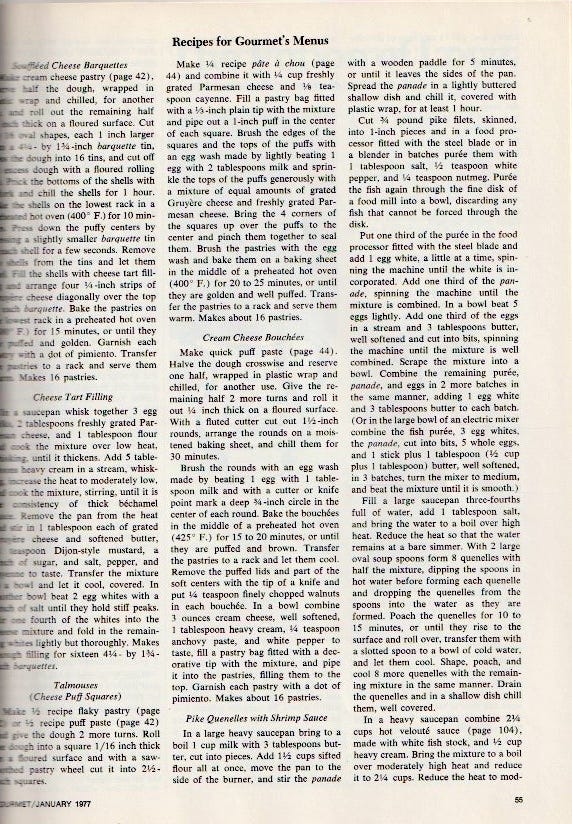

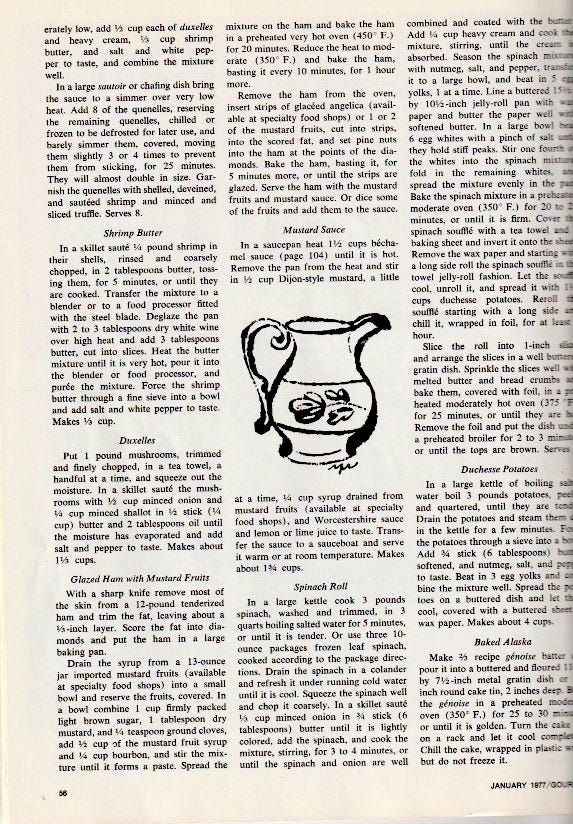

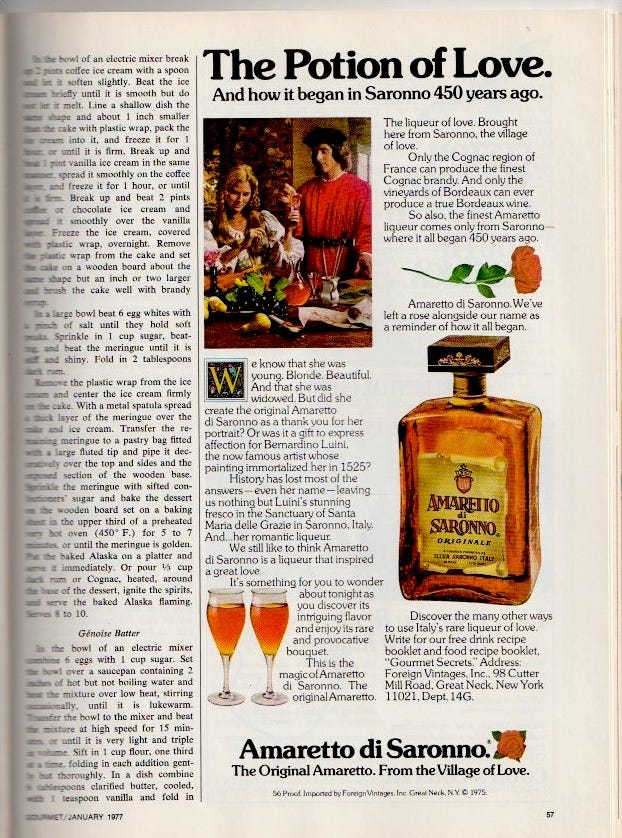

In the spirit of the season I offer this New Year’s Buffet from Gourmet Magazine in 1977. Many dishes here I’d happily serve today. Happy new year one and all!

And in a more practical vein…

We were a big group last night – lots of children – and I wracked my mind trying to come up with a recipe everyone would like.

Then I thought of the Venetian pork ribs I learned to make when I was shooting Adventures with Ruth. Because you have the butcher cut baby backs in half – lengthwise down the middle – they make wonderfully child-sized ribs. (You can do this with a cleaver, but it’s much easier to ask the butcher to run them through the bandsaw.)

I worried that the children wouldn’t like the rosemary and garlic, or that the faint lingering flavor of wine would put them off – but they ate like wolves.

Venetian Pork Ribs

2 pounds baby back spare ribs, preferably from a humanely raised pig, cut into 2 inch lengths

1 teaspoon sea salt

freshly ground black pepper

2 tablespoons olive oil, separated

5 cloves garlic, thinly sliced

rosemary

1 cup dry white wine

cup water

Ask your butcher to cut a couple of racks of baby back spare ribs in half so that you have four racks measuring about 2 inches in width, or do it yourself with a cleaver. Then cut between each rib so you have a great many small, individual pieces.

Dry them as well as you can and sprinkle them all over with salt and pepper.

Coat the bottom of a skillet with olive oil and saute the ribs over high heat until each one has become crisp, brown and fragrant. You don’t want to crowd the pan so you will probably need to do this in two or three batches. Remove the ribs to a platter as they become crisp.

Add the thinly sliced garlic and a bit of chopped rosemary to the empty pan and worry it around until it becomes really fragrant. Put the ribs back in (a single layer is best, so you might need a couple of pans), add the white wine and about 3/4 cups of water. Bring the liquid to a boil, cover the pot tightly and simmer over low heat for an hour and a quarter, or until the pork is entirely tender.

Just before serving, remove the lid and if there’s still a lot of liquid reduce the sauce to a lovely shiny glaze.

Serves 4.

Let’s not forget my personal culinary hero, Caterina de Medici, who contributed immensely to French cuisine from her Italian roots. She brought béchamel, crepes, duck à l’orange, and so much more to France from her Tuscan kingdom (French and Italians still argue over who created these classics, but it was her doing along with the Italian chefs she brought to France). She’s even responsible for the use of the fork when dining! That’s like inventing the wheel in the history of food : ).

I would add the Norwegians and Leif Erickson and the Chinese. The Norwegians are thought to have traveled to the New World where they fished without limit--and kept it a secret as to where they found all this fish), mastered the art of preserving cod which was plentiful in the North seas, and the Chinese are credited with the methods for extracting salt from the earth... I would say that without salt, food would neither have been preserved for long travel across the seas or for ever tasting as good!