What Chefs Talk About When They Talk About Food

Something for fans of Under the Tuscan Sun. A vintage menu. A truly memorable dish.

In 2011 I sat down with Eric Ripert, Jean-Georges Vongerichten and David Bouley to discuss how their cooking had changed over the years. Reading this now, I’m stunned by how much has changed since I wrote the article. And also by how much has not….

When David Bouley walks into the photo shoot an hour late, the other chefs laugh. "You're always late," Eric Ripert says. "You don't change at all."

But they have changed, these three great chefs. Twenty years ago Jean-Georges Vongerichten had just opened his first restaurant, the minuscule JoJo, in New York City, hoping that his reputation for making French food lighter by replacing butter and cream with vegetable stocks would bring customers flocking. Had you told him he'd become the head of a vast restaurant empire stretching across the globe, he would have said you were insane.

In 1993, Eric Ripert's destiny as a major media star was also far off in the future; newly arrived at New York's Le Bernardin, he was helping legendary chef Gilbert Le Coze change the way restaurants served fish. "Gilbert was a purist," Ripert says. "For him, fish was so delicate and sacred, he didn't even want to cook it." Nobody could have foreseen that Le Coze would die, tragically young, of a heart attack in 1994, leaving his sister, Maguy Le Coze to carry the torch. She and Ripert have made Le Bernardin The New York Times' longest-running four-star restaurant.

And in 1991, the remarkably sensual menu at Bouley had already transformed New York's food sensibility, but David Bouley had yet to discover the Japanese aesthetic that would transform his own. "The purity of Japan will change the world," he says now—and the others nod in agreement.

In the intervening years, each chef has had a profound effect on the way we eat. "I came from France in 1986," says Vongerichten, "to cook French food. But I looked around and thought, ‘This food's too rich and the meals are too long; the Italian restaurants are packed—we have to change."

They took their French training and turned it inside out. In France, technique was everything, but in America, they began putting ingredients first. And when the ingredients didn't exist, they changed that, too. "In those days," Vongerichten says, "the farmers would come into your restaurant with seed catalogs: `What do you want us to grow for you next year?' "

Now the ingredients they requested—lemongrass, heirloom apples, black currants, baby beets—are widely available, and the competition to invent the latest, coolest cookery is intense. The four of us sat down to talk about how things were, how they've changed, and where they're going, in the obsessed world of haute food.

Q: How have restaurants changed since you came here from France in the '80s?

Eric Ripert: The position of the chef has changed a lot. It was like a mini revolution. In Paris, I worked with Joël Robuchon, and if you are coming to Robuchon, you will eat what Robuchon gives you. And you shut up, as a client.

David Bouley: It was so different back then in New York City. People used to walk in thinking they were going to tell the waiter what I should cook for them.

Jean-Georges Vongerichten: Really, it was Le Bernardin that changed things.

JGV: [Le Coze] would die before he made something he did not want to cook.

DB: He was very progressive....

ER: Now the client comes to you because they like your style. And young eaters are adventurous and curious. They come in for an experience.

DB: They challenge you.

ER: And at the same time, they don't mind being challenged.

Q: Have prices changed?

JGV: At the time, there were only a few fine-dining restaurants. Five, six, seven. Now there is more competition. I was doing more expensive food in 1988 than I'm doing now. At the first New York restaurant I worked in, Lafayette, the tasting menu was $150; today at Jean Georges it's $148.

ER: That's pretty interesting when you consider how the prices have gone up. Back then, you could buy sea bass for $2.50 a pound; today it's $8 or $9.

Q: How have ingredients changed?

JGV: Everything is so much more eclectic. I discovered grains in New York. In France, the only grain I knew was wheat. In the early '90s I had a Jewish girlfriend, so I thought I'd make a variation of kasha varnishkes.

ER: New York is so cosmopolitan, with so many different nationalities; you're getting inspired by the Koreans, the Irish, the Japanese, the Jewish, and the Latinos.

DB: Robuchon was using soy sauce in 1981, you remember? No other French chef was doing that. Now everybody does.

JGV: Soy sauce and butter—it's the best sauce in the world. Bring a spoonful of each to a boil and add lime juice.

Q: How will we eat in the future?

ER: Molecular gastronomy is dead. Our generation is all about the primacy of ingredients. Things keep getting lighter. Escoffier meant to make food lighter by replacing meat stocks with butter and cream. Then nouvelle cuisine came along, trying to make food lighter by taking away the butter and cream. And then, Jean-Georges, you made it lighter with the vegetable juices. Today, there's the Japanese influence, making the food lighter again.

Q: Okay, last question: Women in the kitchen? Has that changed?

DB: It's totally a coed environment now. That macho thing? It's over.

JGV: They do come, the women, but they don't stay; the drop-off is enormous. It's very hard to be a mom and a chef.

DB: It requires a lot of sacrifice. But I notice that women understand complex things faster than some of the guys. They get it like that, in a second. It's amazing.

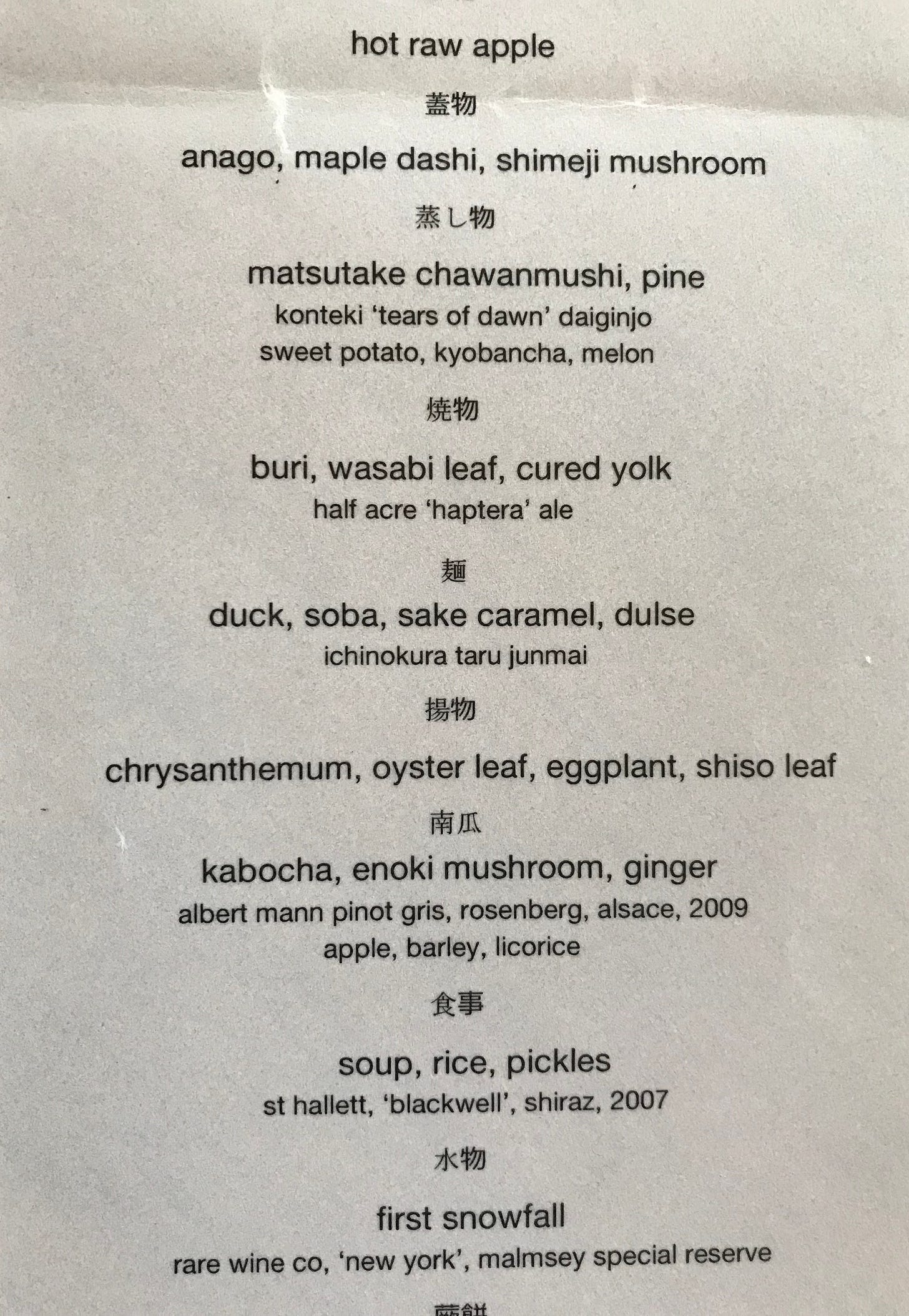

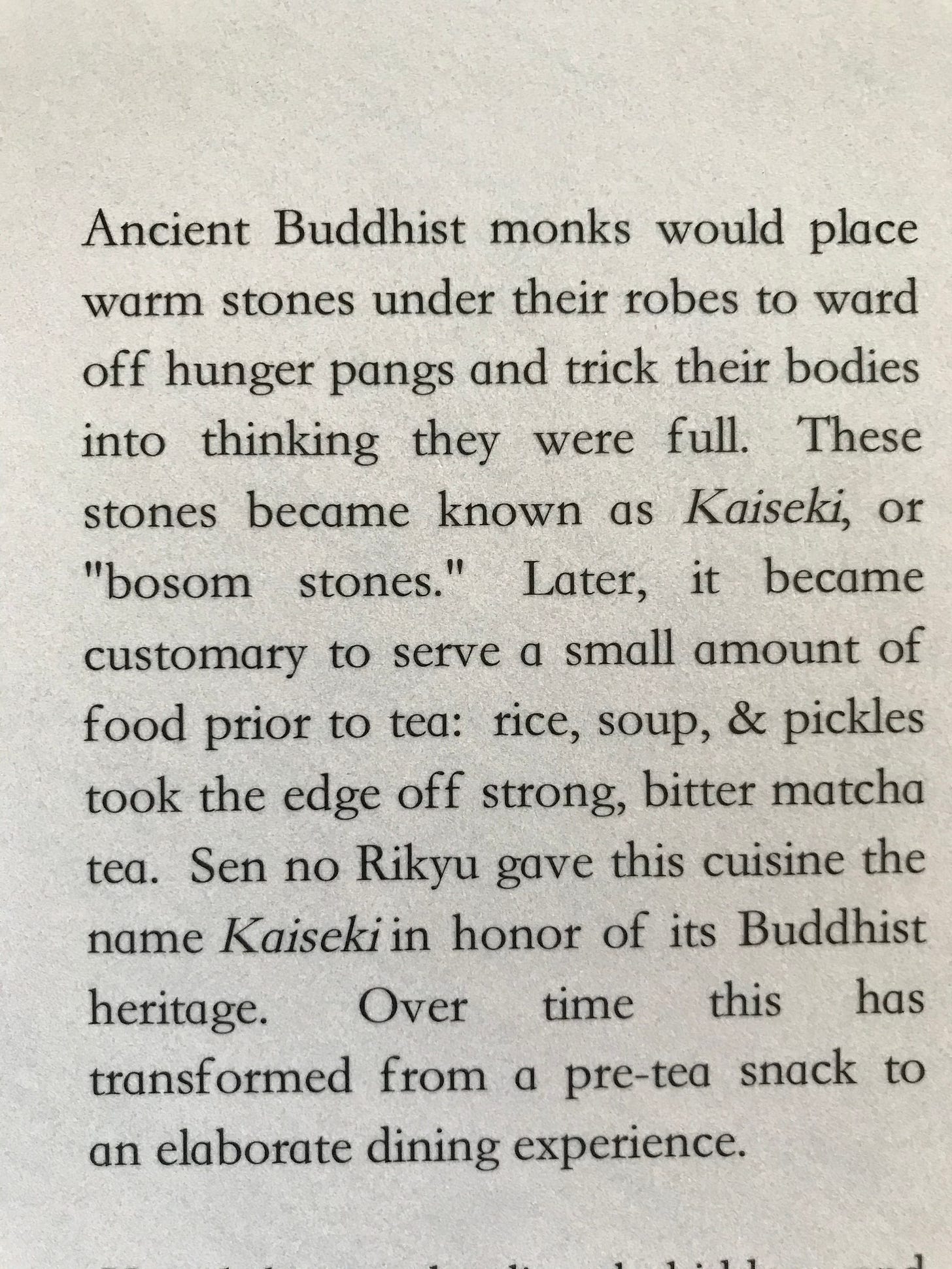

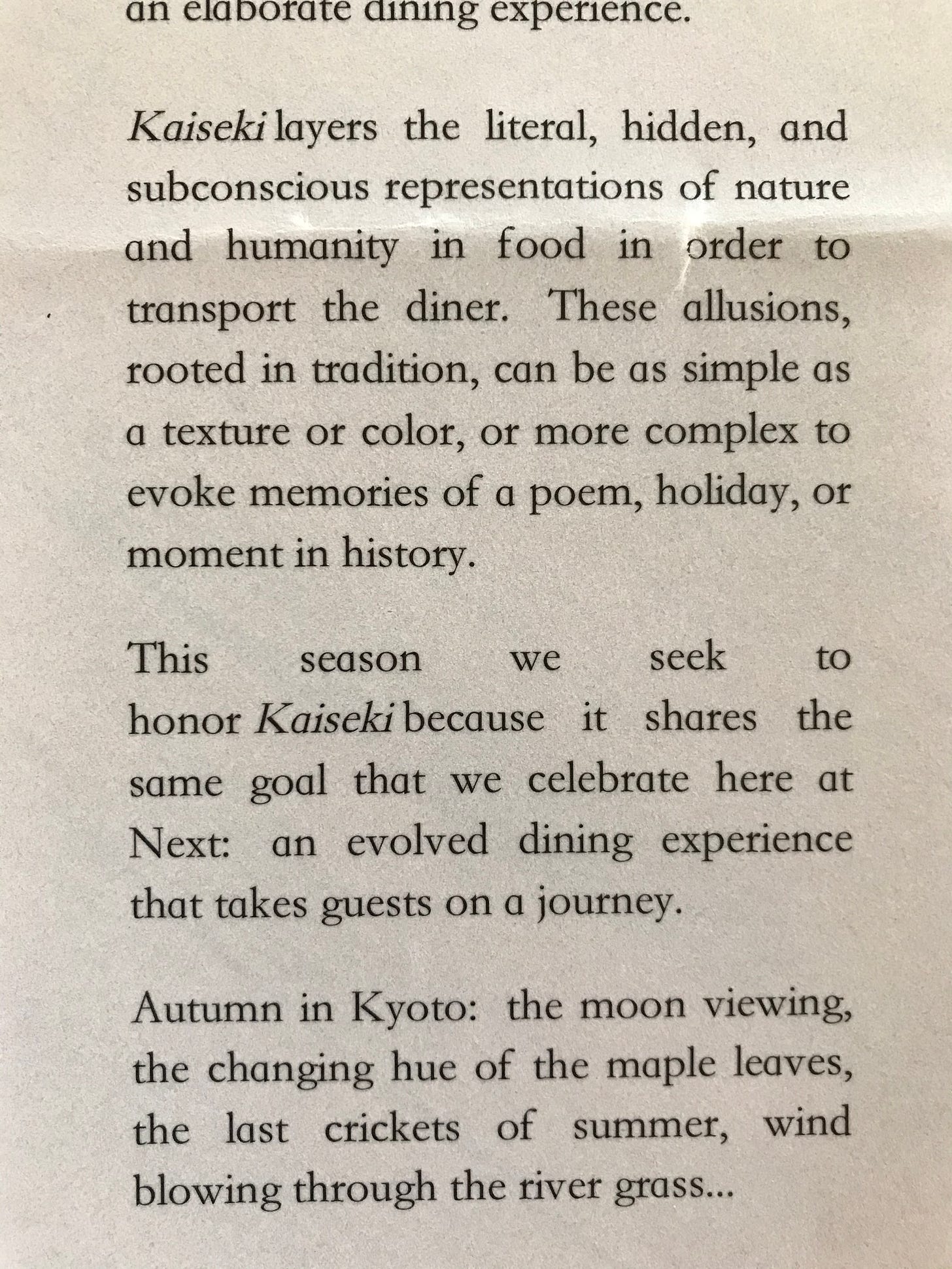

Speaking of the Japanese influence… In 2013 Chicago’s Next restaurant decided to explore kaiseki cuisine. Grant Achatz and Dave Beran went all in, creating this beautifully mysterious trailer to entice us all into going.

It certainly worked on me; I flew to Chicago for dinner. I was very glad that I did.

I’ve never met the author of Under the Tuscan Sun, but Frances Mayes and I will be doing an event together in Denver in November. A few days ago, and very unexpectedly, she sent me a bottle of her own olive oil.

Bramasole Extra Virgin Olive Oil is wonderful stuff - shipped straight from the Mayes’ Tuscan home. It has a lovely aroma and that characteristic zing that hits the back of your throat. The website is all worth spending some time with; there’s a newsletter and many fantastic recipes.

The oil’s not cheap, but through Monday you can get 10% off by using code PASTAVELOCE. Your salads will thank you.

My favorite dish - in a week of astonishingly fine food - was at Coast to Coast, an event sponsored by the Los Angeles Times featuring many of the best chefs from New York and Los Angeles. There were many memorable partnerships (I particularly liked the one between Justin Pichetrungsi of Anajack Thai and Trigg Brown of Win Son). But this dish, by Chef Ton of Bangkok’s Le Du Restaurant is the one I can’t stop thinking about.

Hiding beneath that pile of Thai herbs is a tender little shrimp. That glowing red stuff? Savory beet sorbet laced with fish sauce, clam juice and a hint of chile. The flavors, textures and temperatures danced around in your mouth in the most intriguing fashion. I’m going to attempt a version of that sorbet; I’ll let you know how it works out.

Just to bring this full-circle: Chef Thitid “Ton” Tassanakajohn worked with Jean Georges (and a lot of other New York chefs). Here’s a fascinating interview with him. Read it at your peril; it made me long to eat in Thailand.

Great edition! I just got a used Pacojet on eBay and I want to try the beet sorbet!

Luv the chef interviews!