How Japanese Food Changed Our Tastes

Also, a perfect recipe for a cold winter morning. And an homage to great French chefs.

I ordered takeout sushi last night, and as I bit into excellent uni I began thinking about the enormous impact Japanese cuisine has had on the way we eat in America. It made me go back and take a look at the foreword I wrote to the 25th anniversary edition of Japanese Cooking: A Simple Art.

I wonder if I can even begin to explain to you what the world I lived in – the world of food – was like when I first picked up this book?

Let me try. Imagine this: If you were a restaurant critic at the time, you did not need to know about anything but the food of France, along with a smattering of what was then called “Continental Cuisine” thrown in for good measure. It is hard to conceive, in this age of supermarket sushi, but back then Japanese food was so unfamiliar to Americans that Shizuo Tsuji felt obliged to tell his readers that they would find sashimi “unbearably exotic, almost bordering on the barbaric.” While urging them to taste it, he conceded that this would require “a great sense of gastronomic adventure and fortitude.” He was convinced that the only people with any real understanding of his native food were those who had already visited his country.

But even those of us who had not visited Japan were aware that most people were transformed by the experience. It seemed to me that this was especially true for people who cared about food. The chefs of France, who had all gone off to taste sushi and tempura, had been so captivated by the Japanese esthetic that they changed the way they cooked. Like French artists at the turn of the century, whose contact with the art of Japan had literally offered a new perspective on the world, the great French chefs of the 1970s and 80s returned from the east and began to radically rethink their art. Traditional French cooking had been a way of bending nature to the will of man, but now the chefs began to look at what they were doing from a different position. For centuries the French had been focused on the arcane chemistry of the kitchen, but now they began to emphasize the integrity of ingredients. Influenced by Japan, Nouvelle Cuisine put nature first and insisted upon a new reverence for simplicity.

It was a virtual revolution in dining. The classic three-course meal of rich and generous dishes based on butter and cream was elbowed aside by a parade of exquisitely spare little dishes. How did Americans react? Most people made fun of it. There were jokes – endless jokes – about the portions being so small that you had to go out to dinner after dinner when eating Nouvelle Cuisine.

Like so many food writers of the time, I was intrigued by this new approach to cooking. But I was even more excited by the changes it entailed. This emphasis on simplicity meant that chefs went looking for new sources for their products, and embraced an entirely new universe of ingredients. Menus began to change. Tableware changed too, for this food spoke to the eye as well as the mouth, giving the plate an entirely new place at the table.

Before long American chefs also began making their way to Japan. The first I heard of this was during an interview I was conducting with Paul Prudhomme for a story on Cajun cuisine. Paul couldn’t stop talking about a kaiseki dinner he had been invited to in Tokyo. It was, he said with a kind of awe, the most expensive meal he had ever eaten, and by far the most beautiful. And it included dozens of exotic, exciting and unfamiliar ingredients. Listening to his sonorous voice I began to feel that I too needed to go to Japan and taste the food for myself.

But I knew that I could not make the trip without doing some serious preparation. I understood that the only way to truly experience this traditional cuisine was to learn the rules before I went. I asked Japanese friends for help, and through them I began to learn the correct order of the Japanese meal. I discovered that it progressed in methodical fashion from the simplicity of clear soups and sashimi to increasingly complex dishes, before ending up with the jolt of vinegared salads and then slowly winding down again with rice, miso soup, pickles and tea. I struggled to get my mouth around the difficult syllables - suimono, aemono –and to memorize all the things you were not allowed to do with chopsticks (never, ever, leave them upright in a bowl of rice). I tried to remember not to put sushi in the soy sauce rice-side down, and to abstain from sake when eating rice.

One friend translated an entire book of restaurant reviews for me, circling the best places to eat soba, ramen and tempura, and noting with some pride that many of these venerable establishments had remained unchanged for hundreds of years. When I asked about the kaiseki food that Prudhomme had described, he shook his head and said that it was extremely unlikely that I would be allowed to experience that particular pleasure. The great kaiseki restaurants, he explained, offered a kind of edible poetry served on antique dishes, and one could not simply call up and make a reservation: Introductions were required. And then, on the off-chance that I might manage to wangle a reservation for one of these exalted establishments, he told me that protocol demanded that I go to the bank beforehand so that I could pay the (enormous) bill in crisp, new, consecutively numbered bills.

All this, of course, only made me more eager to visit the mysterious country where eating required such esoteric knowledge. What I did not discover, until I actually went to Japan, was that the great lessons of the Japanese kitchen had absolutely nothing to do with style and everything to do with substance. The real lesson of Japan was learning to live with the seasons. And that, of course, meant finding out what was growing all around you.

I suspect that is why, when I asked Mary Frances Fisher what advice she had to give me before I left for Japan, she handed me this book. “Everything you need to know is right here,” she said.

“But it’s a cookbook,” I replied. “I’m not going to be cooking in Japan.”

“No,” she said simply, “it is much more than a cookbook.” And then, in her sphinx-like way, she did not say anything more.

She was right of course; this is much more than a cookbook. It is a philosophical treatise about the simple art of Japanese cooking. Appreciate the lessons of this book, and you will understand that while sushi and sashimi were becoming part of American culture, we were absorbing much larger lessons from the Japanese. We were learning to think about food in an entirely new way.

Did we know it at the time? I don’t think so. I don’t think we truly understood that the kind of eating in which the diner is constantly making value judgments – this is the moment for sea urchins, this the time of year to eat monk fish liver –turns almost everything that Americans once thought about food on its head. To truly appreciate Japanese cuisine means learning to appreciate quality and paying attention to every bite. What we were learning, when we started eating Japanese food, was that to truly eat well you must open up all your senses and become aware of the world around you.

When Mary Frances Fisher handed me my copy of this book she said, “Read this, and you will understand why Japanese food is important to you.”

I cannot put it better.

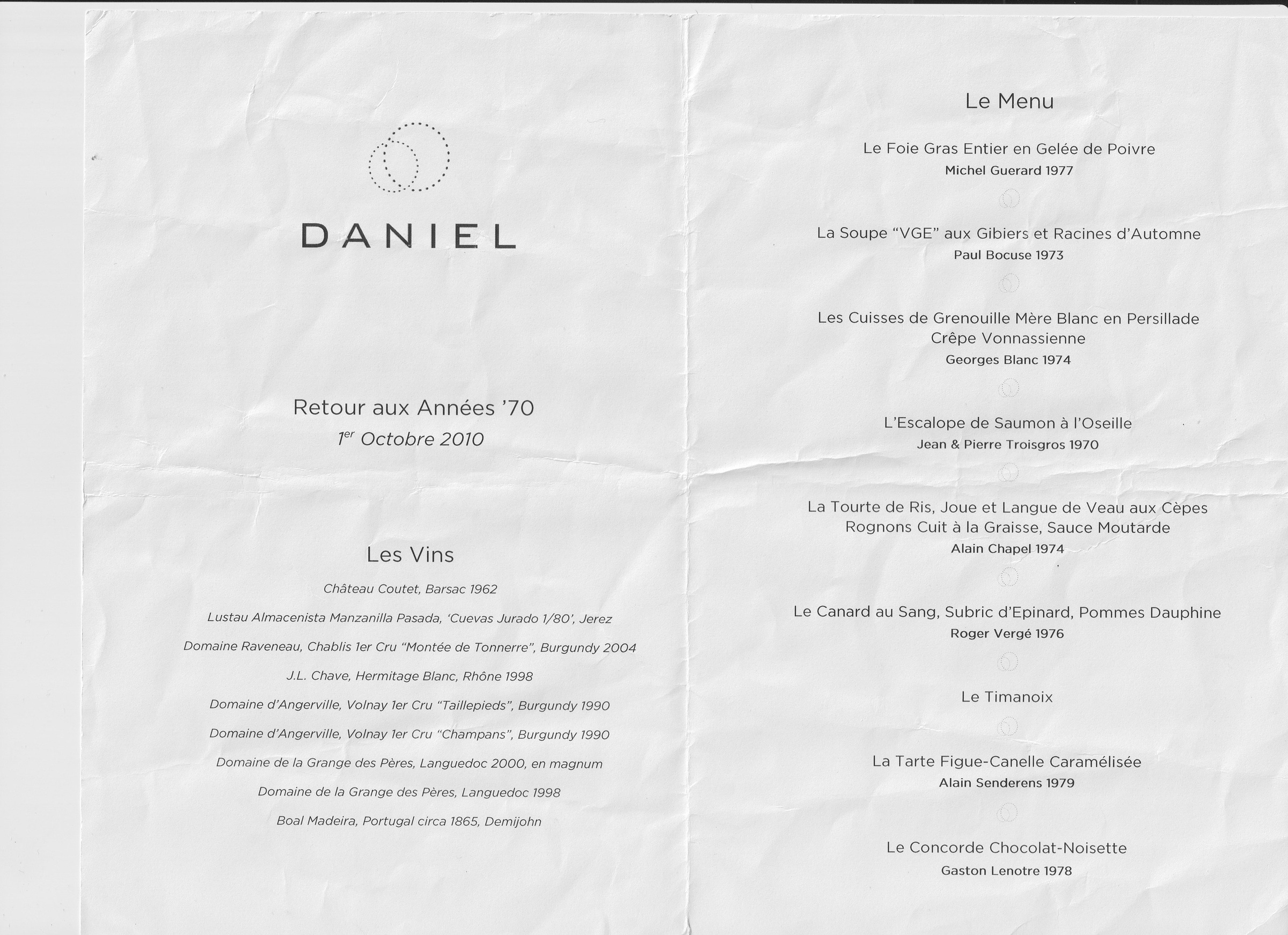

The year’s just turned, and I’m feeling nostalgic. Which is just how Daniel Boulud was feeling when he created this menu, in 2010, to honor the great French chefs of the nouvelle cuisine period.

What an amazing meal this was! (If you want a recipe for the famous Paul Bocuse soup, you can find it here.) And just look at those wines!

Speaking of Japan….can you spot the dish that is a perfect example of the Japanese influence on French cuisine?

Since nostalgia seems to be today’s theme, let’s consider a totally wonderful and very old fashioned dish. Perfect for a cold winter morning.

Shirred Eggs with Potato Puree

4-5 Yukon potatoes (about 1 pound)

one teaspoon sea salt

freshly ground pepper

3/4 cup cream

1/2 stick unsalted butter (4 tablespoons)

4 eggs

Peel the potatoes and cut them into half-inch slices. Put them in a pot, cover them with an inch of cold water, and add a teaspoon of sea salt. Bring the water to a boil, reduce it to a mere burble, and cook for 20 minutes, until the flesh offers no resistance when you pierce it with a fork.

Drain the potatoes and put them through a ricer. Or mash them really well with a potato masher. In a pinch, use a fork. Season with a light shower of salt and pepper.

Melt the butter and stir in a half cup of cream. Now comes the fun part. Whisk the cream mixture into the potatoes and watch them turn into a smooth, seductive puree. Season to taste, doing your best not to gobble them all up.

Heat the oven to 375 degrees and put a kettle of water on to boil. Butter 4 little ramekins and put about a half an inch of potato puree in each. Now gently crack an egg on top of each (being careful not to break the yolks). Set the ramekins into a deep baking dish and pour the boiling water around them (being careful not to splash either the eggs or yourself). Set the dish in the oven for about 8 minutes, or until the whites have begun to set.

Spoon a tablespoon of the cream over the egg in each ramekin and bake for another 5 minutes or so, or until the egg whites are set but the yolks are runny. Garnish with flakes of salt, bits of chopped chive, or if you're inclined to true indulgence, crisp crumbles of bacon.

When I lived in Seattle in the late 1960s and '70s there was (and is) a very good Japanese grocer, Uwajimaya, that offered Japanese home cooking classes which I enjoyed immensely - and, of course, was able to easily get ingredients. Then I lived in San Diego in the 1980s and '90s and there were quite a few excellent Japanese restaurants there (esp sushi). Being on the West Coast with the much larger Japanese population certainly made all the difference. Now in the ethnic wasteland of Vermont I am feeling quite deprived.

And the shirred eggs w/pureed spuds look amazing.

OMG that recipe sounds like a “slut” served at Egg Slut - a poached egg served atop a potato purée! So enjoying your posts :)