Two weeks ago, on Thanksgiving, there was Mom, standing with me in the kitchen. “Your turkey’s going to be overcooked,” she lamented as I set the timer for four hours.

“Mom,” I said, “this bird weighs 24 pounds!”

She shook her head. My late mother had some extremely strange notions on cooking. Although no turkey on the planet will cook in under an hour in an ordinary oven, Mom refused to believe that. Let me just say that Mom’s turkeys were never dry.

“And what are you doing now?” she asked, peering over my shoulder. I was squeezing pomegranate juice. Nick, the grandson Mom never met, loves the sweet tart gravy I first made when he was six, and it’s been a staple on our table ever since. As I was silently explaining this to her, I was startled by a thought: what makes our ritual meals so powerful is not that we gather with our families, but that we gather with our ghosts.

My kitchen was especially crowded this year. Aunt Birdie was standing next to me as I creamed the onions. “Do you remember,” she asked, “the first Thanksgiving you ever cooked?” How could I forget? She was 100 years old, and we had to carry her up the stairs. “I don’t remember that” she sniffed. “What I do remember is that we were all thrilled when you agreed to do it. And that you were very nervous.”

Well of course I was! When the meal moved from Mom’s house to mine, it seemed like a major rite of passage. It was 1970, and the first time I really felt grown up. I fussed about, desperate to get every detail perfect. It wasn’t: as I remember, the turkey was dry, the mashed potatoes lumpy. But that was the day I learned the single most important fact that every home cook needs to know. “We didn’t come to eat,” Aunt Birdie told me gently, “we came because we wanted to be together and share a meal. We’re grateful when the food is wonderful, but it really doesn’t matter. Remember that.”

A while later, as I was scrubbing sweet potatoes, a few friends from my Berkeley years came through the door. “Remember,” Jules said, “that time we decided we were vegetarian?” I certainly did. It was 1976, and what I remember most is that preparing enough vegetables to feed fifty made us understood why so many holiday meals involve a single, giant piece of protein. Thanksgiving that year was an exhausting production, and by the time it was over our vegetarian days were too.

I roasted chestnuts, crushed cranberries, peeled potatoes; with each step some old friend was at my side. As I sharpened my knife the late Michel Richard, one of the finest chefs I’ve ever known, suddenly appeared. “So slow!,” he said, watching my careful slices. The man could carve a bird in ten seconds flat. I timed him once. Each slice was perfect. That was in the early eighties, but I’ve yet to meet anyone who could beat him. And there he was, back again, making gentle fun of me.

My ghosts stayed with me, flitting in and out of the kitchen as the day went on. And even later, doing dishes, I found that I was not alone. A few years ago, when all the guests had gone, I handed Laurie a dish to dry. My old friend held it for a moment and then blurted out, “The doctors say I’ve only got a few more months. This is my last Thanksgiving.” I miss Laurie — I always will — but this year she was with me at the sink, just like always, another visitor from Thanksgiving past.

This gives me great comfort. Years from now, when I’m long gone, I know that Nick will be standing in a kitchen carving turkey. Maybe he’ll be an old man by then, cooking for his grandchildren. But it’s nice to know that I’ll be there.

Speaking of memories….

This isn’t food, and it won’t improve your cooking. But SPUR has made me very happy this year, and I thought I’d pass the info on.

Like so many people, I inherited jewelry from my grandmothers, my aunts, my mother. I wear my grandmother’s locket almost every day, and it gives me great pleasure, making feel that my family is with me, cheering me on. But my other grandmother’s jewelry is far more ornate than anything I’d wear, and I have pins, necklaces and watches that have languished in my jewelry box for years.

Then I heard about a company that takes your old jewelry and refashions it to fit your lifestyle.

Looking through their site I saw what beautiful work they do, creating wedding rings and the like. But I wanted them to do something rather different than their usual task: take my ornate pieces from a hundred years ago and refashion them into something simple I can wear every day.

Let me just say that I have not taken the necklace they made me — a simple white gold chain studded with my ancestors’ gems — off since the moment it arrived. Now I feel as if Mom, both grandmothers and my Aunt Birdie are always with me.

If you know someone who has old jewelry sitting around, a gift certificate would make a truly inspired gift.

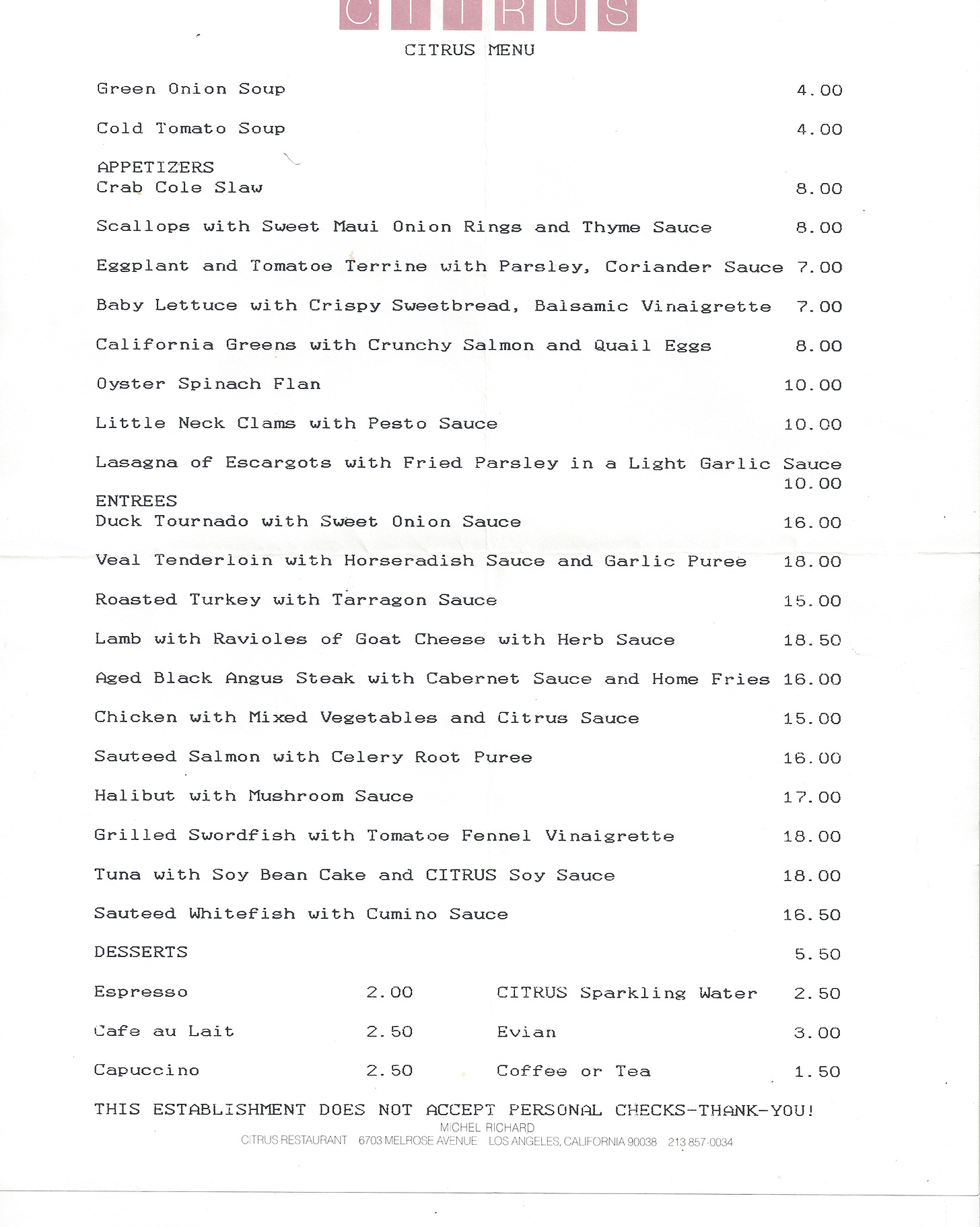

When Michel Richard dropped in at Thanksgiving (see above), I started thinking about his first restaurant, Citrus, in Los Angeles. He was the most inventive cook — nobody ever had more fun cooking— and Citrus was always full of surprises. Michel thought of the menu more as a suggestion than a blueprint; he was constantly inventing new dishes. This menu must be from the year the restaurant opened, 1987.

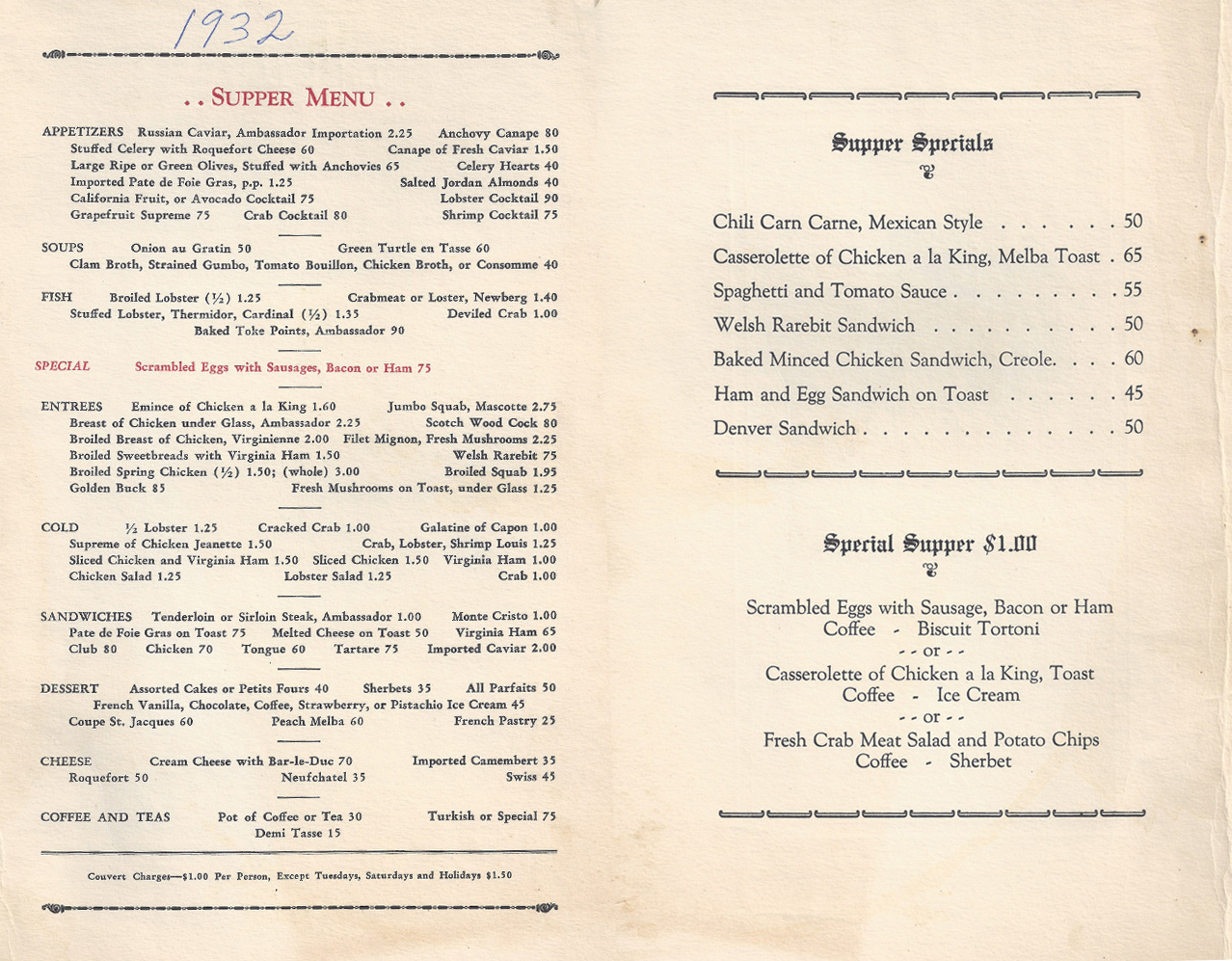

And I thought I’d add a menu from Aunt Birdie’s time. (Aunt Birdie passed away in 1980 at the age of 102.) she was the one who gave me this menu from 1932. Some of these prices are astonishing: olives cost more than chili con carne, and grapefruit was more expensive than a ham and cheese sandwich!

Love, love, love this piece. Having grown up in a big boisterous extended family where holidays were gatherings of often 30 or more, moving 3000 miles from home to retire makes holidays bittersweet. Cooking with Ghosts comforts me and reminds me to hold my ghosts close. Thank you for your new newsletter; I've missed you being at the LA Times, LOVED Save Me the Plums, and am giddy that you're offering yourself here, for now. Mine is a grateful heart!!!

I’m having tea with Ruth’s mom as we speak. She says Ruth was always a good girl and she is very proud of her, within limits. She says Ruth is an excellent cook notwithstanding her insisting on overcooking the turkey for days until it is dry as a bone. She tried to teach her to soak the turkey overnight, rub margarine under the skin and fill the cavity with lemons (just regular lemons, not the fancy ones that her so-called friends use). She never said to cook a turkey for an hour. Ruth exaggerates. But three hours is plenty and any more is a waste of electricity. These kids. Berkley! And why couldn’t she leave perfectly good jewelry alone? It’s like she always says, if it isn’t broken, why fix it? But what is she going to do? She doesn’t want to rule from Beyond. Sit up straight Ruth and would it hurt you to put a comb through your hair? Again, she is very proud.