Spicy Chinese!

The woman who changed the way we cook it. Also, where to buy the best Ingredients. Vintage menus. Great books. And a super simple, satisfying recipe.

When I bought my first Sichuan cookbook, I was in heaven. It was 1974, and The Good Food of Sichuan made it possible for American home cooks to attempt what was then a fairly arcane cuisine. Although it was difficult to source authentic Chinese ingredients back then, I worked my way through the cookbook and it changed the way we ate at my house.

My first encounter with Fuchsia Dunlop was equally impactful. Today Fuchsia is a beloved institution, but when her first book, The Food of Sichuan was published in 2001 she was virtually unknown. The book, which was revised and reprinted five years ago, was unlike anything else on the market and once again the food at my house was better because of it.

Fuchsia’s latest book, Invitation to a Banquet: The History of Chinese Food, is essential reading for anyone with a serious interest in food. Her Instagram feed is endlessly entertaining, and her recipes are terrific.

As you will see from the article below, I met Fuchsia when she was just starting out and instantly signed her up to write for Gourmet. (If you want to read some of the early pieces Fuchsia wrote for Gourmet, you will find them here. )

“I know you’re interested in Chinese food.” Guy Diamond, editor of Time Out London, was sharing lunch with me at a modest Indian restaurant. “I have someone I really think you ought to meet. Her name....” he looked slightly embarrassed, “is Fuchsia.” He lowered his voice, adding, with all the diffidence of a slightly shameful revelation, “…hippie parents.”

Was he trying to sell her short? I wondered; it takes a rare editor to hand a talented writer off to another editor, even when their magazines exist on separate continents. “She’s the only Westerner to graduate from the great Sichuan cooking school in Chengdu.” This was said a bit reluctantly, and I understood the context; Fuchsia was too good to keep to himself.

It was the early aughts, and Gourmet already had a long history of fine writing on Chinese cuisine, written by native authors exiled from their country, or curious cooks who had studied in Hong Kong or Taiwan. In the eighties the magazine ran a ground-breaking series of articles by Nina Simonds. But Fuchsia was different; she was trained in a corner of the Chinese Mainland few of us had visited - and she was passionate about the food.

She wrote stories for us on restaurants in Chengdu. She wrote stories for us about Chinese restaurants in London. She wrote about ingredients and parts of China that were then unknown. But when she called to say she was escorting a trio of master chefs to the United States, I was particularly excited. “How would you feel about taking them to dinner at The French Laundry?” I asked.

She hesitated. “I’m not sure that they’ll like it,” she demurred.

“That,” I said, “is the whole point.”

I anticipated culture shock, thought they might treat the fare in one of our greatest eating institutions with the puzzled repugnance Americans reserve for unfamiliar foreign dishes like jellyfish and goose intestines.

But I was unprepared for the depth of their disgust.

The chefs thought olives were nasty, like a dose of the bitterest Chinese medicine. Rare lamb was worse. “Dangerous,” was one chef’s assessment. “Terribly unhealthy,” opined another. They were puzzled by oysters, found cheese revolting and considered salad food for savages.

They found the length of the meal almost unbearable, and half an hour after getting up from the table complained they were hungry again. There was only one remedy: they set off to find the nearest plate of scallion-fried rice. (Fuchsia’s article, Culture Shock, is here.)

Chinese Fried Rice For Two (adapted from Fuschia Dunlop)

You need cold cooked rice to make this dish; it won’t work with warm rice. Leftover rice from Chinese takeout is perfectly acceptable, although it tastes better with higher quality Jasmine or Basmati rice.

Get a wok really hot and swirl in a tablespoon or so of peanut, roasted rapeseed, or grapeseed oil. Add the chopped whites of a couple of scallions, and when they’re fragrant, add 2 large eggs, lightly beaten, and tilt the pan to form an even sheet. It should set in about half a minute; add 2 cups of cooked rice, a half teaspoon of salt and stir fry for a couple of minutes, breaking up the egg sheet. Allow the rice to rest, unstirred, on the pan for about 10 seconds between stirs, so it gets crusty.

Add the thinly sliced scallion greens, and a small splash of sesame oil.

One day when I was at Bonnie Slotnik’s wonderful cookbook store I encountered an incredible multi-volume Chinese Food Encyclopedia that had been printed in Japan. After I'd spent hours perusing the Sichuan volume page-by-page, I had no option but to walk outside and head a few blocks south into the first decent Sichuan restaurant I encountered. What did I order when I got there? Mapo tofu of course.

Though the whole encyclopedia was printed in Japan, this volume was written entirely by Sichuan writers. Each of the recipes comes from one of the best restaurants in the province. This is Grandma Cheng's, the institution credited for popularizing the dish:

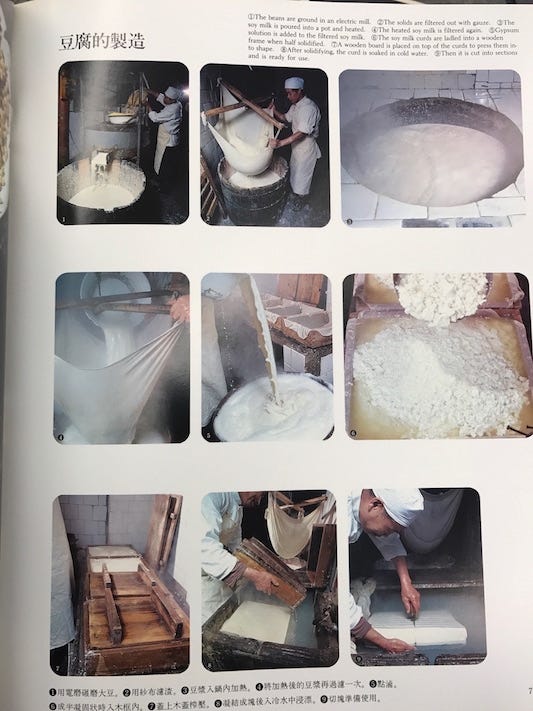

There is also an article about the factory where the restaurant’s tofu is made; reading it I couldn’t help remembering the soy milk factory I visited in Tai San in 1980. Here’s what I wrote in my journal:

“The center of village nightlife is the soy milk factory, which is also a sort of cafe. They sell the tofu as it is made, still warm, slightly sweetened, with a bit of peanut oil. But the factory’s main activity is to take the just-made curd and turn it into skins. The curd is spread onto a long conveyor belt in a thin layer. It travels for about 18 feet, slowly, as it is steam-heated. At the end of the line the slightly wrinkled sheets are peeled off. These dried tangles are what you see in shops everywhere, a veritable staple of local food.”

Bruce Cost (yes, the ginger ale guy), is not Asian, but he’s one of the finest Chinese cooks I’ve ever encountered. His book, Asian Ingredients was first published in 1988 and then revised in 2005; it is an excellent guide for people looking to cook authentic Asian food.

For years Bruce produced a Chinese New Years banquet for Chez Panisse; here’s the menu from 1987.

American home cooks have grown so enamored of Asian food that most supermarkets now sell a range of very decent ingredients. But they can’t compare to the ingredients you find online at The MaLa Market. Frankly, I don’t know how I managed before this incredible resource opened.

Where to begin? The four products I use most often (after their chiles, fermented black beans and Sichuan peppercorns) are the 3-year old Pixian Chili Bean Paste (doubanjiang), which is so so superior to the black bean paste with chiles I’d been using that it has absolutely transformed my version of Mapo Tofu. They also sell real Oyster Sauce (most commercial oyster sauces contain no seafood), which makes almost every savory dish taste better. The minute you toss a couple of tablespoons of their roasted rapeseed oil into a hot wok your kitchen starts smelling like a Chinese restaurant. It has a deliciously toasty aroma unlike any other oil I’ve encountered. I never want to be without it. And their various black vinegars are all fantastic.

Can’t decide? Ma La Market has a number of different kits. But be warned: once you start using their products, you’re never going back.

You can make your own pork and chive dumplings, or you can buy one of the always disappointing brands that now take up more and more space in supermarket freezers.

But why would you do either of those things when you can probably go to Chinatown and purchase huge bags of frozen dumplings from your favorite restaurant at shockingly reasonable prices?

I’m sure there are great places for frozen dumpling in every Chinatown in America. In New York I go to Supertaste, where I indulge in a bowl of noodles while I’m buying a bag of 50 frozen dumplings. (And I happily plunk down another $3 for a container of the very delicious dipping sauce.)

I am sure, Ruth, that you know this: Fuschia is about to lead a culinary tour of Yunnan. It is one of those she leads three times a year (I think) for a company called Wild China. My son, Francois, and I went on one of her tours in May of this year. Apart from having to taste more foods than I can, the experience was fabulous.

What a quick and easy fried rice recipe! I just finished reading The Paris Novel, loved it, and am interested in cooking again!