Can We Talk About Tipping?

The best prime rib. Fabulous potatoes. And behind the scenes at a restaurant collective.

A couple of weeks ago I had dinner with a group of friends at a restaurant I greatly admire. I love the food. The service is excellent, the prices reasonable. At least I thought they were reasonable. The prix fixe menu trumpeted “hospitality included,” and when I mentally calculated 20% off the price of dinner, it struck me as a real bargain.

Then the check came. To my surprise, right below the total was an empty line that said “tip.” As I sat there trying to figure out what to do, I grew increasingly annoyed. Behind me I could hear the people at the next table discussing the situation. “Don’t tell me the tip’s included and then ask me for a tip,” the woman grumbled.

It made me think once again, about the whole ugly problem of tipping.

I began waitressing when I was in college, and I thought tips were wonderful. At my other job — shelving books at the campus library — I worked a twenty hour week and took home $20 (before taxes). Working at Ann Arbor’s fanciest restaurant, on the other hand, I always made at least $40 during my 4 hour shift. No wonder I thought it was the greatest job on earth: I got paid ten times what I earned at my other job, and dinner was included.

I stopped waitressing after college, always tipped generously and did not think very much about it until last year. At the height of the pandemic some six million restaurant workers lost their jobs. Sixty percent of them were not eligible for unemployment benefits because their wages were too low. When you find out why, you think about tipping in a new light.

When the minimum wage was first instituted in the 1930’s, restaurant workers were exempted. To this day servers in forty states are paid a sub-minimum wage of $5 an hour or less; in some states servers earn as little as $2.13 an hour. Tips are supposed to make up the difference between what people are paid and the salary they ought to be earning. Since those tips aren't recorded, an unemployment benefits system based on what you make gets thrown out of whack. But that is just one issue. Think about this for a minute: the hospitality industry is the only industry in America where employees are not actually paid by their employers, but by the customers they serve. What does that mean?

It's true that servers employed in high end restaurants often earn so much that those in the kitchen feel cheated, but they are a small and privileged lot. The vast majority of American servers are women and people of color employed by fast-casual restaurants across the country. They have to answer to their bosses — and every individual boss who orders a dinner, a glass of wine, a cup of coffee. If their customers don’t feel like tipping, there’s nothing they can do.

The result? Even before the pandemic left millions unemployed, tipped workers relied on food stamps at twice the rate of other workers. And the system is rife with abuse. I’m horrified when I look back at the uniforms I was often required to wear. Low cut blouses. Very short skirts. High heels. I remember one particularly awful cocktail waitress job where I gritted my teeth every night as I smiled and backed away from groping hands. But what’s a waitress to do? If you’re only earning $2.13 an hour, you need those tips, and only one person in that transaction has power.

I didn’t mean to go off on this particular tangent. It all started with a self-righteous rant about being annoyed when a no-tipping restaurant included a line for a tip. But now that we’re once again facing restaurant closures, I’ve been thinking about what will happen to all those out of work waiters. And it is very clear that the system needs to change.

It reminded me of one reason I love traveling to, say, Japan. Service there is not an economy — or a culture — built on tips. You don’t tip taxi drivers, waiters or bellboys. You don’t tip chambermaids. Should you try, you are politely refused. It’s a point of pride. People do their jobs, they are paid by their employers, and power is not part of the equation.

And if you’re wondering if I left a tip at that no-tipping restaurant a couple of weeks ago…. Of course I did. I used to be a waitress.

I love prime rib, but I only cook it once a year, for a grand holiday meal. And then I splurge on the best. This arrived yesterday, a well-aged prime rib from De Bragga.

With meat this good, you don’t need to do much. Remove it from the refrigerator three hours before you’re going to cook it, slather it with salt and pepper and put it in a very hot oven (450 degrees) for 20 minutes. Turn the oven down to 325 and cook until the internal temperature is 115 degrees (for rare meat). That should be a total of about 10 to 12 minutes a pound, but it will depend on the shape of the meat so use a thermometer. Let it rest about half an hour before carving. Eat with enormous pleasure. And look forward to next year.

And here’s my favorite potato dish to serve with the roast.

The secret to these potatoes is that they’re cooked twice. First you plunk them into a big bath of milk and cream that’s been infused with just a touch of garlic and bring them gently to a boil. Then you dump them into a baking dish, grate a bit of fresh nutmeg over them, and sprinkle the entire top with Gruyère before putting them into the oven where they drink up all the liquid as the cheese turns into a crisp crust.

Potatoes au Gratin

SHOPPING LIST

1½ cups cream

2½ pounds boiling potatoes (such as Yukon Gold)

½ pound Gruyère cheese (grated)

STAPLES

2 cups milk

2 cloves garlic (smashed)

1 teaspoon salt

pepper

whole nutmeg

butter

Pour cream and milk into a large pot. Peel the potatoes and slice them as thinly as you can, putting them into the pot as they are ready. Add the garlic, the salt, and a few good grinds of pepper and bring it all slowly to a boil.

Meanwhile, butter a gratin dish or a rectangular baking pan. When the milk comes to a boil, remove it from the heat and pour the contents into the buttered gratin dish. Grate a bit of fresh nutmeg over the top and cover with grated Gruyère cheese.

The baking is pretty forgiving; you can bake at anywhere from 300 to 400 degrees, depending on what else you have in the oven. The timing’s forgiving, too; at the lower temperature it will take about an hour to absorb the liquid and turn the top golden, at 400 degrees it will take about 35 minutes.

Let it rest for at least 15 minutes — but this, too, is forgiving. If the potatoes have to wait an hour, they will be absolutely fine.

Serves 6 to 8

Click HERE for a printable recipe

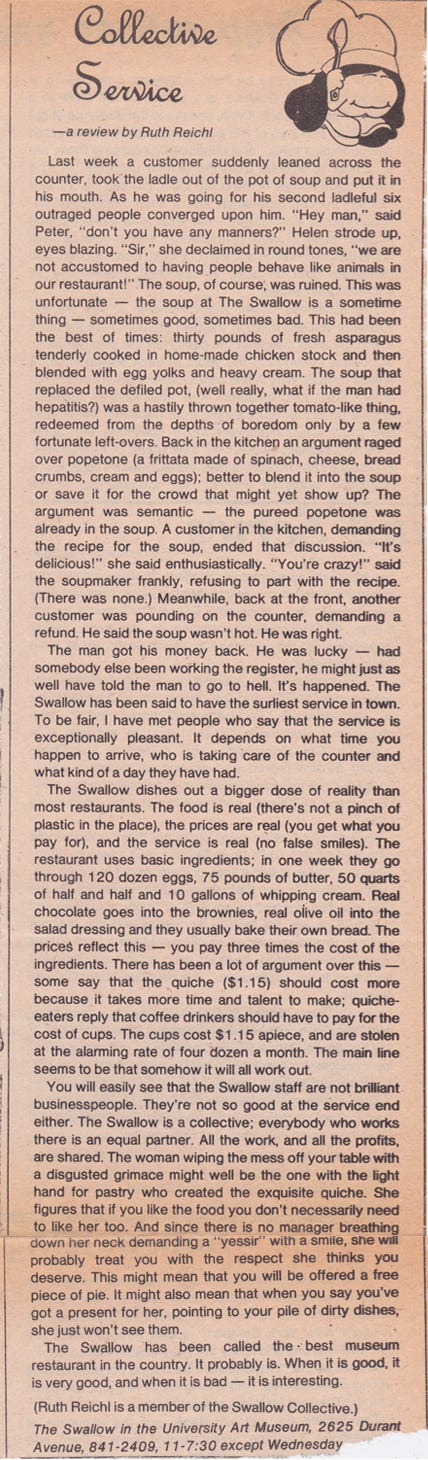

Since we’re talking about tipping, here’s a view from the other side. I wrote this around 1975, when I was a member of The Swallow, a collective restaurant in Berkeley. It was published in The East Bay Review. (I wrote for them for free, hoping to get some clips so I could one day get a real writing job.) To be honest, I’m kind of stunned they printed this piece. It is a very real slice of life in that restaurant.

I worked at the Swallow in the 80s, shortly after you left, Ruth. It was still exactly as you describe it here. Thanks for the memories! I’ll never forget having an insurance salesman come in to sell us health insurance. He asked for the manager. I said, “I’m one of them.” He proceeded to brag that his plans didn’t cover abortion or contraception, hence lower premiums. Took me 10 seconds to shoo him out the door.

Re Tipping: I spent 25 years in the kitchen and am a good tipper now. Recently I was reviewing my work receipts and noticed a receipt that had 18% (I think) added to the check due to us being a larger party. Well I didn't notice that and tipped another 20% on top of it! Thank God it was the company card and not my personal card. LOL