A few years ago the Museum of Modern Art mounted a show of Cezanne’s paintings. They asked if I would write something for their newsletter. I instantly knew what I wanted to write.

Cezanne turned me into a food writer.

But it was not for any of the reasons you might imagine.

In the late sixties, when I was a graduate student in art history, my professors were constantly dropping the names of restaurants near great monuments of art. I wrote them all down: the trattoria five minutes from Giotto’s murals in Assisi (“get the ribollita”), the bistro around the corner from Notre Dame that served fantastic choucroute, and the five-hundred-year-old tofu specialist near Kyoto’s Kinkaku-ji. And it was while studying Klimt that I first heard of Demel, Vienna’s venerable emporium of pastry.

The art historians I studied with also enjoyed deconstructing the many meals depicted in art. Together we devoured endless last suppers, along with the painted feasts of Bruegel, Vermeer and Veronese. They discussed artists like Orozco and de Heem, who used food as both allegory and a means of illuminating ordinary life. And when one professor announced that his next lecture would be devoted to the food of Cezanne, I could hardly wait.

We walked into the room to find a slide of Cezanne’s Apples on the giant screen above our heads. “Cezanne,” the professor began, “once told a friend that fruits ‘love having their portraits done’.” We all stared up at the painting as he continued. “Cezanne also said that he wanted to ‘astonish Paris with an apple’.”

I concentrated on that image, waiting to be astonished. But hard as I tried, those apples left me cold. Cezanne’s apples, I soon discovered, were not apples; they were painted strokes on a canvas, and he did not want you to forget it. That was the point.

I understood what the artist was up to. That painting was about art, not apples. It was about the impossibility of ever making two dimensions truly resemble three. It is an interesting intellectual idea, and in the context of art history, an important one. But the more I stared at that painting, the more I began to wonder if I wanted to spend the rest of my life thinking about such things.

I left that class in a state of confusion. It was a beautiful fall afternoon, and as I walked back to my apartment, I couldn’t shake the feeling that there was something wrong with me. Shouldn’t a person who planned to be an art historian appreciate Cezanne’s apples? Passing a local grocery store I noticed a fine display of Ida Reds, Arkansas Blacks and Esopus Spitzenburgs. They were beautiful; astonishing, in fact. But I had no desire to contemplate those apples; all I wanted to do was eat them. I bought as many as I could carry, determined to transform them into something delicious.

At home I peeled the apples, listening to the seductive way they came whispering out of their skins. I sliced them and showered them with lemon juice, leaning into the citric scent. Constructing a crumble, I concentrated on the way the butter became one with the flour. And then, surrounded by the heady aroma of sugar, butter and fruit swirling through my kitchen, I opened my notebooks and began to read.

The evidence was all there: I was looking at art but focusing on food. I was clearly not meant to be an art historian. Much as I enjoyed studying art, my true passions lay elsewhere. By the time the apples emerged from the oven, my life had changed.

I still don’t like Cezanne as much as I think I should. But I am very grateful to him. Had I not encountered his apples on an autumn afternoon in Ann Arbor, I would probably be teaching art history today.

I’d be happy enough, and yet… deep down I would be aware that my life had gone wrong.

Apple Crumble

In the early fall, when apples fill the trees, they are best served without much embellishment. Later in the year you might want to tuck them into pastry, roast them into sauce or stuff them into the mouth of a suckling pig. At this time of the year, however, less is definitely more.

A recipe this simple requires a few different varieties of excellent apples. Try for heirlooms that not only have different flavor profiles, but also react differently to heat. I like to blend apples that maintain their shape when cooked (Arkansas Blacks, Ida Reds), and some that go into a slump when they encounter heat (McIntosh, Golden Delicious).

Apple Crisp

5 heirloom apples

1 lemon

2/3 cup flour

2/3 cup brown sugar

salt

cinnamon

6 tbsp unsalted butter

Peel a few different kinds of apples, enjoying the way they shrug reluctantly out of their skins. Core, slice and layer the apples into a buttered pie plate or baking dish and toss them with the juice of one lemon.

Mix the flour with brown sugar. Add a dash of salt and a grating of fresh cinnamon. Using two knives (or just your fingers), cut in the butter and pat it over the top.

The cooking time is forgiving; you can put your crisp into a 375-degree oven and pretty much forget it for 45 minutes to an hour. The juices should be bubbling a bit at the edges, the top should be crisp, golden and fragrant. Serve warm, with a splash of cream.

I’ve written about my love for apple cider syrup before, but it’s apple season, and I can’t resist mentioning it again. This is a classic American ingredient that deserves more attention.

When the Jamestown settlers waded ashore they were carrying pots of apple saplings; the young trees thrived and by 1900 there were seventeen thousand varieties of apples growing in America. This was partly due to John Chapman – a Swedenborgian missionary and entrepreneur known as Johnny Appleseed - who devoted himself to spreading the apple gospel. But contrary to legend, he wasn’t planting apples for pies and sauce; his were destined for the cider press.

For much of American history water was considered too unsafe to drink. Some people relied on beer, but the beverage of choice was hard cider (even children drank it).

Cider also had other uses. Boiled down it turned into a deep, dark syrup that was perfect for pies, cakes, baked beans, and classic desserts like Indian pudding and mincemeat. During the Revolution cider syrup became even more important; since sugar and molasses were imported from British plantations in the West Indies, patriotic Americans stuck with their home-brewed sweetener.

Then the Civil War came along and people in the north abstained from cane sugar and molasses because they were products of the slave trade.

But during prohibition cider syrup production came screeching to a halt as sober citizens chopped down apple trees to prevent the manufacture of demon hard cider.

That is definitely our loss. Cider syrup, in my opinion, is far more appealing than molasses, agave syrup or maple syrup. Put a drop on your tongue and you taste apple blossoms, honey, and citrus. Simultaneously sweet and tart, it has a slight caramel edge and just a touch of smoke. A drop makes vegetables sing, turns ordinary applesauce into something extraordinary, tastes great on pancakes and gives the dullest ham real character.

My favorite is Carr’s. Here in the Hudson Valley you can find it in many local stores, but it is also easy to order online.

And if you’re looking for recipe suggestions, here’s one.

Roasted Butternut Squash with Apple Cider Syrup

Cut the squash in half, which is the hardest part of this entire recipe. Remove the seeds and strings, put it in a foil-lined roasting pan, cut side down, with a little bit of water and roast at 400 degrees for about 45 minutes. Let it cool, then squish it out of the skin and mash.

Add 2 or 3 tablespoons of butter, salt and pepper to taste and allow the butter to melt. Splash in some of the syrup; I use a couple of tablespoons, but you might want more.

At the very end, I like to stir in some pomegranate seeds, which adds both color and crunch.

Serves 4.

While we’re thinking of apples and anticipating autumn…

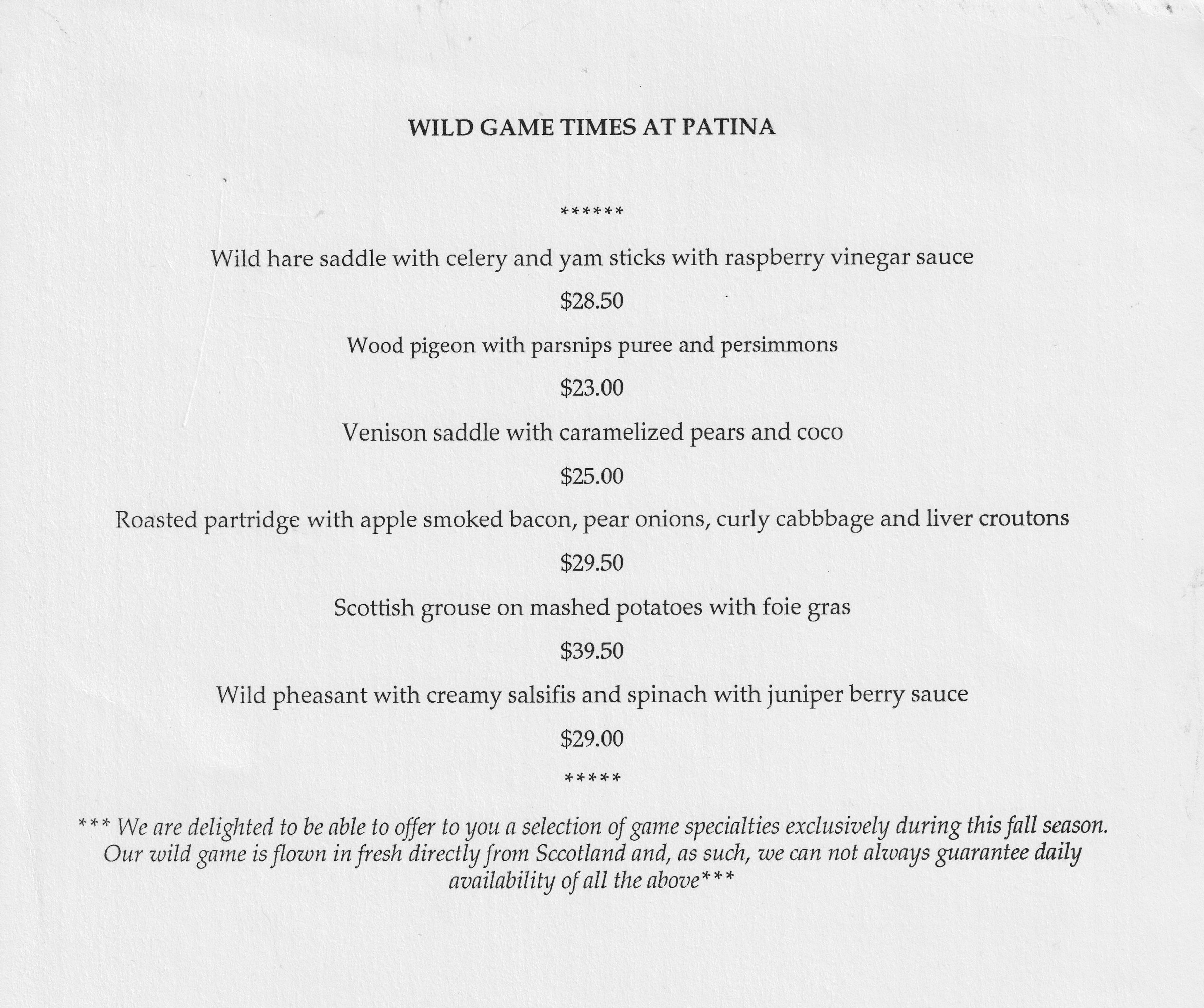

This intriguing menu is from Joachim Splichal’s Los Angeles restaurant in the early nineties, when Tracie des Jardins was chef de cuisine. (Here’s my review of the restaurant at that time.)

If you’re going to be in the Hudson Valley soon come join me at Meet the Makers at Hudson Hall on Thursday the 21st. I’ll be on a panel about food and farming with Max Morningstar from Morningstar Farm, Alex Napolitano, chef at The Maker. and William Li. The event is free but reservations are recommended.

On September 28th I’ll be presenting my film, Food and Country at the Woodstock Film Festival.

Planning to be on the West Coast at the end of October? I’ll be participating in a couple of big food events there. The Ojai Food and Wine Festival takes place the last weekend of the month. It’s very star-studded (and very expensive), but I can promise you a few deliriously delicious days.

The following Monday, October 30th, it’s La Chef Conference, which is no less star-studded but a lot more affordable. It’s a full day of great food, good fun and interesting panels. Proceeds from this benefit Re:Her.

And finally, a reminder about the Dream Trip to Paris contest I wrote about a few weeks ago: it’s not too late to enter. The proceeds go to ending hunger in Maine and the prizes are swell. Read about it here.

I grew up in a farm town that was mostly orchards and cow pastures, and the cows went away in the 80s. Other than hiding a jug of cider at the back of the fridge so it turns (or leaving it on the porch for a couple days, but DO NOT leave it in your car even if it's "pretty cool out"; I spent $300 getting my car cleaned after $8 of lively cider exploded in the trunk last year), cider syrup is the cider recipe I've used the longest, and one of the things I love to do with it is combine it half and half -- more or less, it depends on how sweet and tart your syrup is -- with decent bourbon, which turns it into a sort of cider liqueur that's great on ice or in a toddy.

Gosh I miss you and Gourmet Magazine! I’m so grateful for your

Posts here and your books. We are traveling now but when I get home Apples will be abundant and I must try this recipe. Thank you!