Alone in the Kitchen with an Eggplant

A tribute to Laurie Colwin. A recipe she'd like. An old menu she'd appreciate. A forgotten cookbook. And a cool meal on a hot night.

Went to dinner at the new restaurant in West Stockbridge the other night, Heirloom Lodge, which is a truly wonderful addition to the neighborhood. As we were leaving chef Matt Straus handed me a copy of the lovely journal he edits, Kitchen Work.

I was a bit stunned to find he’d written a screed about Laurie Colwin… It is pretty much the opposite of they way I think about one of my favorite writers. Well, you’ll have to read it for yourself.

I’ve been a huge Laurie Colwin fan since I first read Alone in the Kitchen With an Eggplant. And I am certainly not alone. When I first arrived at Gourmet I found a huge file - hundreds of condolence letters from fans reaching out to Laurie’s family after her extremely untimely death. One of the first calls I made as editor was to Anna Quindlin, asking her to write about their friendship. You can find that piece here.

But after I read Matt’s puzzling piece I reread the introduction I wrote to the latest edition of Home Cooking. I thought you might like to read it.

People who write about writers have a favorite game. First you have to throw an imaginary dinner party and then dream up the perfect guest list.

Laurie Colwin is always at the top of mine. There’s no one I would rather have at my table. For one thing, she’ll never complain about the food. Laurie (I don’t think she’ll mind if I dispense with the formalities), once loved a man who made scrambled eggs resembling asbestos – and she forgave him. I won’t have to worry about the seating chart either; she was famous for throwing parties in an apartment so small she washed the dishes in the bathtub. As for the menu, I’ll keep it simple. Laurie is definitely of the pot roast persuasion, and has little use for the sort of starters she once described as “some funny little thing on a small plate.” But most importantly, I can’t think of anyone who’s more fun or better company.

You’ve probably noticed that although Laurie has been gone for almost thirty years I’m using the present tense. That is because Laurie is very much alive to me. I see her everywhere. Sometimes she’s standing next to me in the produce aisle, insisting I haven’t bought enough red peppers. (For Laurie there are never enough red peppers.) Sometimes she’s standing by the stove, eying the lamb with deep suspicion. “Rare lamb is disgusting and should never be eaten!” she is saying with that maddening assurance of hers. And each time I go to Chinatown in search of fermented black beans - a passion we share - Laurie is at my side. “Are you going to make my yam cakes with fermented black beans?” she is asking. To be honest, I’m not sure. Like many of her recipes, they’re slightly weird and rather wonderful.

The remarkable thing about all this is that while Laurie is a very real presence in my life, I never met her. This makes me sad; I am absolutely convinced we would have been best friends.

I am not alone in this. Legions of her readers feel this way. Laurie’s great gift is her ability to literally reach through the page and zoom straight into your heart. Her voice is so friendly, so natural, so down to earth that you feel she is talking directly to you.

Still, if you haven’t been reading Laurie’s food essays since the mid-eighties when they popped up in Gourmet Magazine, you can’t possibly understand how much she meant to some of us. Food, back then, was another country, and the people who lived there jealously guarded the gates. There were strict rules, and anyone who wanted to enter had to follow them.

For one thing, special tools with arcane names like chinoise, sauteuse and salamander were absolutely required. Those of us whose kitchens lacked these essential items were not quite welcome. Then Laurie came along and simply blew that notion away. “How depressing it is,” she wrote, “to open a cookbook whose first chapter is devoted to equipment.” She went on to assure us that excellent meals could be made with little more than a knife, a pot, a wooden spoon and a hotplate.

Back then all the important food people agreed that everything tasted better somewhere else. This somewhere else was, of course, Europe, a place they visited with irritating regularity, returning with news of some new ingredient you’d never heard of and could no longer cook without. For those of us stuck here at home this could be very depressing. Laurie, on the other hand, was convinced that good food was just around the corner, and she was always urging you to explore your own neighborhood. Just the way she talked about simple food was reassuring: chocolate pudding was “sincere,” cucumbers tasted “silvery,” and she was convinced that soup came into the world to make you feel safe.

Even after she’d moved out of that little apartment with the dishes in the bathtub, Laurie’s life remained delightfully messy. When she rented a summer cottage the lake was choked with weeds and mice cavorted in the kitchen cupboards. It didn’t bother her. And unlike the other famous cooks with their elegant meals and antique plates, Laurie was not a priestess of perfection.

She gleefully recounted one dinner where the guest of honor said, “this is awful,” and another so misconceived that her guests suggested dumping everything into the garbage and going out to eat. Back then nobody else writing about food would have confessed to these horrors, and you had to admire Laurie’s honesty. It was comforting to know that you can make an awful meal– which of course you’re bound to do– without agonizing over it.

But Laurie didn’t just get over the disasters– she delighted in them. “My life,” she said, “has been much enriched by ghastly meals.” I think of that every time I have a calamity in the kitchen. “It’ll make a great story,” I hear her saying as I stare down at the burnt shards of what was meant to be dinner.

It’s what I love best about Laurie. She may have romanced simple food and offered insights into eggplants, but she understood, better than anybody of her time, that when she was writing about food she was really writing about life. It allowed her to write about the meals she cooked for women in a homeless shelter as just another dinner party. She is feeding people she cares about: end of story.

Now that the world is beginning to catch up with Laurie you may have a hard time understanding what a true revolutionary she was. Consider, for example, the way she ends the introduction. “These essays were written at a time when it was becoming increasingly clear that many of our fellow citizens are going hungry in the richest country in the world. It is impossible to write about food and not think about that.”

It is one of the few things she was wrong about: almost nobody else writing about food in the mid-eighties considered hungers other than their own. What set Laurie apart was her enormously generous point of view. Each of the essays in this book is really about the many ways that food connects us.

I sometimes try to imagine what Laurie would think about the world we live in today, and what she would be writing. I know it would be funny, self-deprecating and delicious. I wonder too, what she would think of the Laurie Colwin cult that has been steadily growing as a new generation discovers her writing. I’m fairly sure it would both delight and infuriate her.

Personally, I think it’s a wonderful thing. The world could use a lot more Laurie Colwins. It would be a better place.

Laurie Colwin and I don’t always agree about recipes; she roasts her chicken for 2 hours…. need I say more?

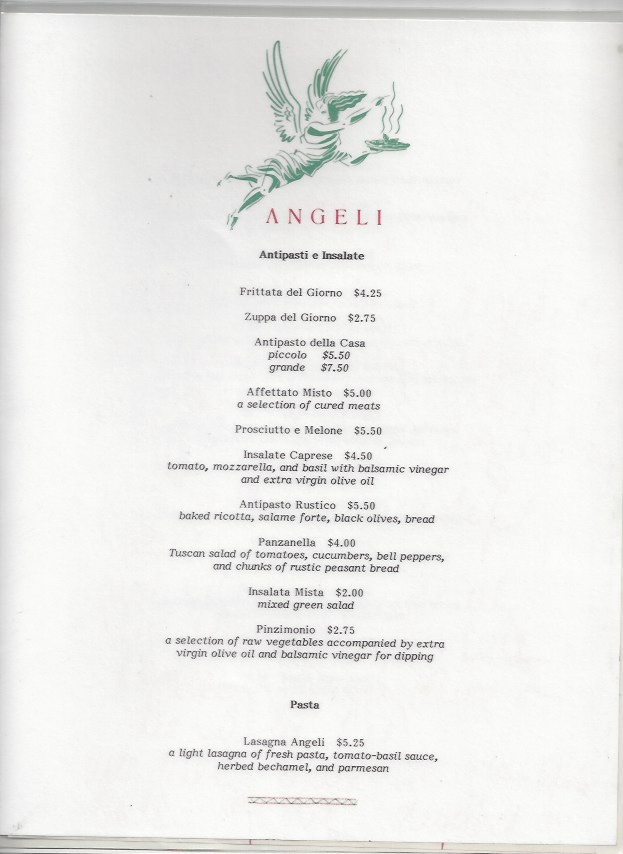

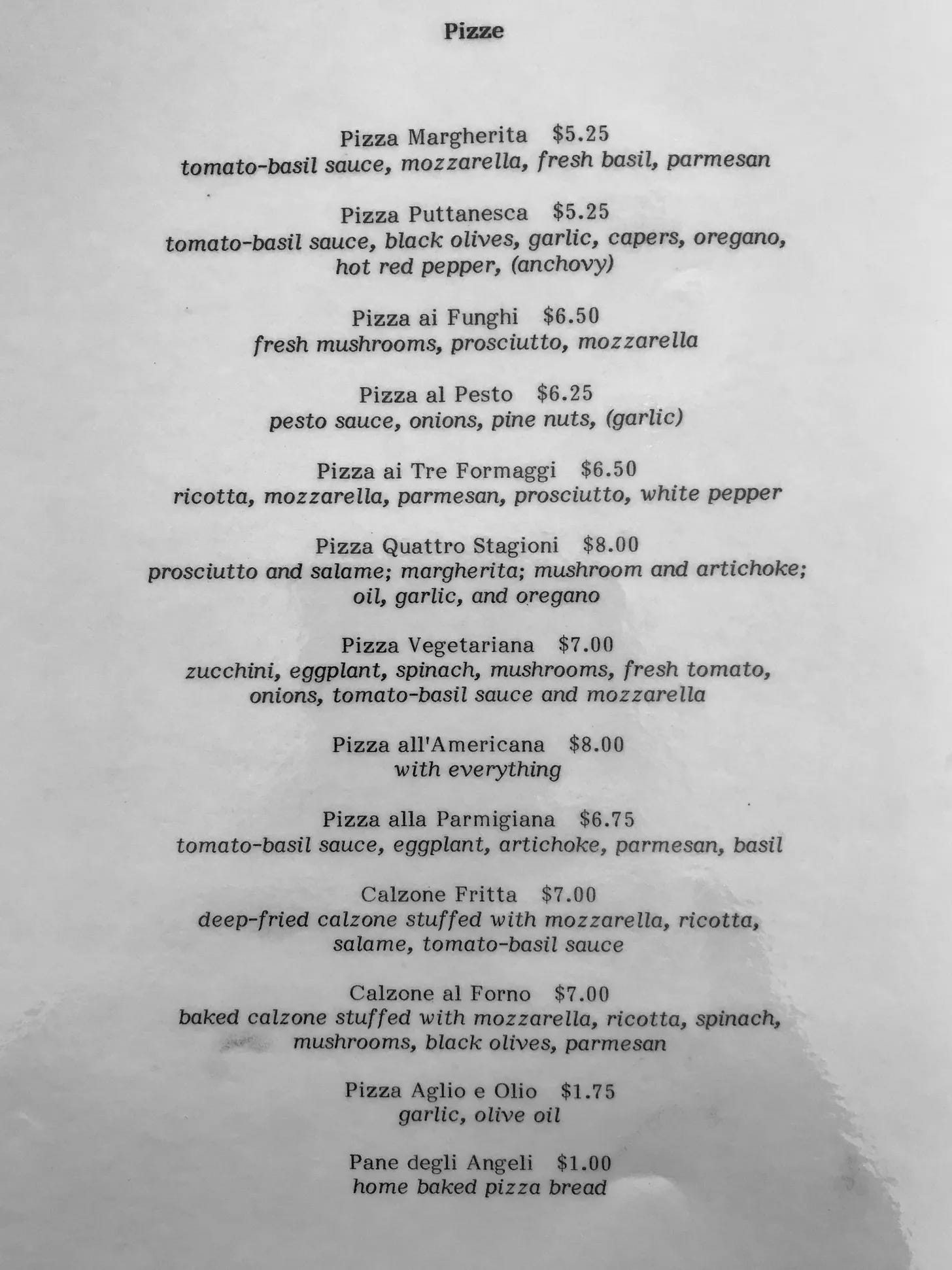

On the other hand, I think she would have been a great person to share a meal with, and had Laurie shown up in LA in the eighties I know exactly where I would have taken her. Angeli.

It’s where I took everyone I really liked; Evan Kleiman’s modest restaurant on Melrose Avenue was unpretentious, inexpensive, and as Marcella Hazan told me at the time, the most authentic Italian restaurant in America. High praise from someone who didn’t hand it out easily.

And Evan and Laurie, I know, would have loved each other.

Laurie Colwin loved eggplants. She loved black beans too. So if she had showed up at my house I would have fed her the dish I learned at the Yangshuo Cooking School in Guilin, China. (The black beans are my own addition.)

Eggplant Yangshuo Style

1 small baby eggplant (about half a pound)

3 tablespoons peanut or rapeseed oil

1 red pepper

2 cloves garlic, smashed or minced

ginger

1/2 teaspoon fermented black beans

1 tablespoon oyster sauce

1 tablespoon soy sauce

3 scallions

Cut the eggplant into long thin strips, then cut those in half. You don’t have to be fussy about this, but you want to end up with pieces about 3 inches long and a quarter inch wide.

Slice the red pepper into thin strips.

Smash the garlic and grate the ginger until you have a couple teaspoons.

Rinse the salt from half a teaspoon of Chinese fermented black beans.

Measure out a third cup of water, then add oyster sauce, soy sauce, and the rinsed black beans.

Slice the scallions into long, thin shards, then cut them into 2 inch lengths.

Get a wok so hot that a drop of water, flicked in, skitters across the surface. Add the oil, swirl it around the pan, then throw in the eggplant slices and toss them about until they’re soft and slightly seared on the edges.

Reduce the heat and add red pepper, the garlic and ginger and toss until the scent rises above the pan, then add the water mixture. Stir fry for a couple of minutes; the eggplant should now be coated with a glossy sauce.

Add the scallion threads, toss for a few more seconds and serve to two happy people.

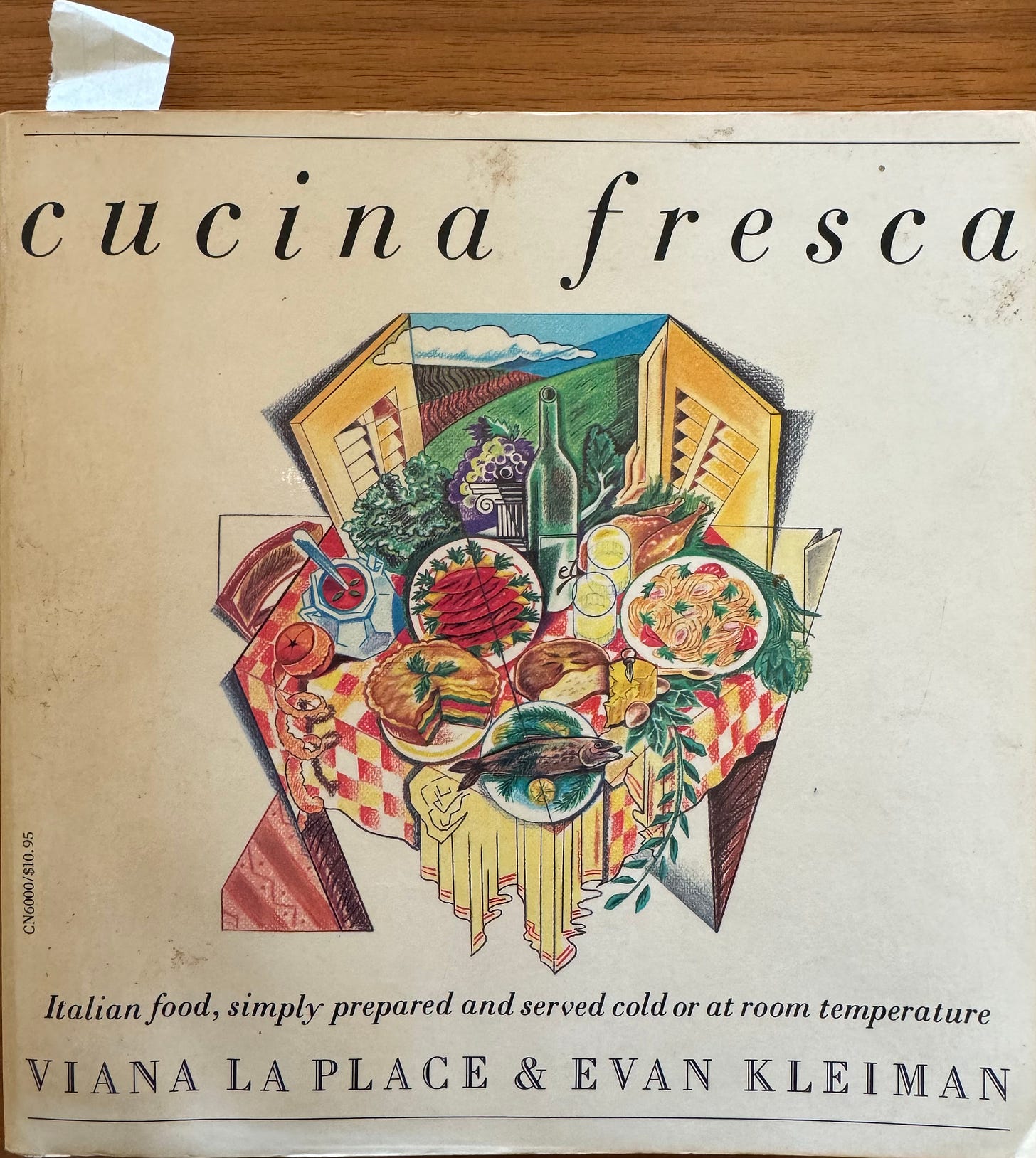

Since I’ve mentioned Evan Kleiman…. I think you should know about Cucina Fresca, the book she wrote with Viana Laplace in 1985.

It’s a wonderful book filled with simple recipes that can be eaten hot or cold - perfect for this particular season. My own copy is dog-eared and stained from many years of very happy use.

It was so hot in New York City last week that I was not surprised to walk into Penny and find it filled with food folk; the marble bar is a perfect place to pull up a stool on a sultry night. After all, they have a dish called Icebox (above).

They also have the best variation on vichyssoise I’ve yet encountered. (Despite its name, the cold, creamy soup was invented in New York in 1917 when Louis Diat, chef at the Ritz-Carlton, wanted something special to serve his customers on a hot night. Diat, incidentally, went on to become Gourmet Magazine’s first resident chef.)

But Diat did not fill his concoction with little pops of roe that turn it into the Champagne of soup. Almost impossible to eat this one without laughing in delight.

I loved everything we ate, but I especially admired this steelhead trout with lovage

And then there was this fantastic ice cream sandwich!

Laurie Colwin is a great treasure. I read her essays when I want to feel cozy and reassured. I wonder what she would think of social media - would she have rejected it or embraced it?

We had a copy of Cucina Fresca when I was growing up. I still remember a favorite recipe that I made often in season, swordfish with tomato salsa fresca. Not sure what became of that book, but I'll need to replicate that dish in about a month, when tomatoes are in full flush here in Oregon.