All About Mmmmm

Notes on my first cookbook. A recipe. A story. And a new Sichuan restaurant.

This article from Publisher’s Weekly was published just as my first book was being sent out into the world. I think it says quite a lot about the state of publishing at that time - and a bit about the state of cookbooks too.

(I should probably note that the book was definitely not a bestseller!)

We did not sleep the week the book was due, working around the clock to meet the deadline. Then we drove uptown, dropped off our pile of camera-ready pages, and headed west. Doug and I were going to Dale Chihuly’s Pilchuck Glass workshop north of Seattle, but we drove slowly, camping along the way.

It was a memorable summer. I posted this piece a few years ago, so apologies to those of you who’ve read it.

We went clear across the country, backroads all the way, Scruff sitting on the dashboard, more like a dog than a Siamese cat. It was July and Route Two was as far north as you could go without being in Canada. The days stretched, long and languorous, the light lasting until ten or eleven every night.

It felt like freedom to be out of New York, out of our cockroach-ridden loft on the scary lower east side, and out of the nine to five of the jobs we hated. Sometimes, as we were rolling through empty cornfields with the sky huge above us Doug would look at his watch and say, “We could be on the Bright D train right now, with some guy standing over us, slowly dripping sweat,” and we’d laugh and think how much we didn’t want to go back.

We took our time heading west, stopping for church suppers in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, where they served us fried chicken and potato salad. We bought pasties – sturdy meat pies – in the little towns we drove through – munching as the miles rolled past. In North Dakota we stopped at the Rosebud reservation, to give our friends the braids of garlic we’d brought from Little Italy; they said garlic was what they missed most about New York, that there wasn’t a single clove in the entire state. We stayed a week, talking, cooking, going to powwows where we ate fry bread and once, something they told me was boiled dog. Was it true? One night Joe came home with a wild turkey he’d shot himself. I’d never seen one, never seen that strangely curving backbone that won’t sit straight in any pan. When it came time to go Joe handed me a star quilt. “Gets cold up there in northern Washington,” he said. “You take this. Our people know about living outside and staying warm.”

Somewhere in Wyoming the radio went dead. It came booming on again, just outside Cheyenne, a Ravi Shankar raga that accompanied us for miles. A good omen, we thought, still worried about what we would find at the end of this journey. We’d done it on a lark, agreed to work at a glass workshop in the wilderness. Some patron of Dale’s had built him a place north of Seattle, and students were coming for the summer. The equipment was all there, but not much else, and Doug was supposed to help the kids build the structures that they’d live in. I would teach them how to cook. No money, but it beat another summer in the city with our shoes sticking to the sidewalk and “Me and Julio Down By the Schoolyard,” playing, over and over in the bodega downstairs, coming through our windows, invading our dreams.

Pilchuck turned out to be the most beautiful place I’d ever seen. And the most primitive I’d ever lived in. My heart sank when I saw the kitchen: it was just a wooden platform with a wall on two sides, and a sink with a washtub hanging over it. We were going to have to gather wood for cooking, build a fire pit, make do. There were no bathrooms either – am I remembering this right? – or is it just that after a while we didn’t use them any more? The forest was all around us, and the clear lake beat any shower I’d ever used. What I remember most is how strange it seemed, later, going back to civilization with its bathtubs and its toilets. Their lack had been another kind of freedom, and I’d liked it fine.

It was frantic at first, a mania of competitive building, everyone intent on making his house into a work of art. Jamie Carpenter went to the town dump, collected every old window he could find and built a treehouse. It was a crystal palace in the sky, an extremely sexy structure. A RISD kid named Tree built a yurt in the middle of an open field. John hollowed out a tree stump and called that home. Doug spent an entire afternoon looking for living tentpoles, then stretched plastic between the trees, creating a transparent house. It was oddly elegant, and from far off in the distance you could see our star quilt, winking out its welcome.

Scruff was a city cat, but his ways were wild. At night he’d creep into the forest, returning with little birds and chipmunks. I was always worried that we’d lose him, but all we had to do was whistle and he’d come running back, jump onto the bed, lick his paws and purr.

The forest embraced us, offering endless gifts. I walked the land, picking black and blueberries for pies and jam. They were everywhere. I went foraging for mushrooms and found lamb’s quarters as well. I stuffed the leaves into my mouth; the flavor was bright green, springlike, so much more delicious than the supermarket spinach we’d been eating. I’d put out pails of milk at night and find yogurt in the morning. Such abundance. To me it felt like magic.

At the Samish reservation we traded glass for salmon. “How you gonna cook that?” a native woman asked, and when I told her she laughed and showed me how they did it there, planking the fish around a fire. I’d never tasted fish like that – sparkling fresh, rich with fat, and very smoky.

I’d brought no pots or pans along, so Dale took me to the Snohomish auction where, for fifty cents I bought the contents of an entire country kitchen. I’d been meant to show the students how to cook, but they were making art, and in the end it was easier to do it all myself. I was very happy.

One day Buster came into my kitchen and watched me try to light a cranky fire. “I’ve got a better idea,” he said, taking my hand. In the workshop he shoveled molten glass out of the furnace, spreading it across a metal table. “Your stove,” he said.

It was two thousand degrees of ferociously glistening heat, and it took a bit of practice, but in a few days I had mastered meat. You had to calibrate the cool; pancakes were easy, eggs very hard. I made mistakes. But the days were long, and nobody cared if we didn’t eat til midnight. We ate right from the pots, mostly with our fingers, and drank straight out of the bottle.

In late August we trooped out to Tree’s yurt to watch the northern lights go flashing through the sky above us, falling, falling. It was beautiful. And sad. Summer was waning, fall coming on. We would have to leave. The patron invited us to a final feast, and we sat around his fancy pool feeling like children at a grown up party. There were crackers and cheese, and the wine was served in glasses. It was very nice, but we were minding our manners, and eager to go back to the forest where there were no rules.

By then we knew, Doug and I, that we were done with the city, although we did not yet know how we would manage the escape.

Leaving was awful, like being kicked out of paradise. We were so depressed as we rolled east that some nights we didn’t bother looking for a campsite. We just pulled over on the side of the road and climbed into the back of the van. One of those mornings I woke to find that we were already moving. “Wait!”’ I said, “Stop. We can’t leave yet. Scruff’s not back.” Doug kept driving. I looked at his face and saw that it was wet. He let the tears fall, watching the road, until his shirt was soaked. When he found his voice he said, “There will never be another cat like him.”

Later he told me that he’d seen the car hit Scruff, that it had happened fast. By then we were in some little diner off the highway. It was small, and smelled like old hamburgers, stale beer and bad coffee. We ordered eggs; they were overcooked. “Summer’s over,” Doug said as he paid the bill.

He was more right than he knew. Dale got famous. Pilchuck got buildings – workshops, dormitories and bathrooms. I suppose that these days there is also a proper kitchen. Students still flock there in the summers, and they’re still blowing glass. But I can see myself in that funny little kitchen with the washtub over the sink. I can feel the sun shining down on me, and hear the wind rustling through the trees. Scruff is twisting through my legs, purring. Me, I’m looking down at the lake, happy to be here – and utterly unaware that I have just learned about all the things that I will never need.

This recipe is from Mmmmm, so I guess that means I’ve been making it for more than fifty years.

Sour Cream Apple Pie

3/4 cup sugar

3/4 cup brown sugar

2 tablespoons flour

1 teaspoon cinnamon

1/2 teaspoon nutmeg

juice of 1 lemon

3/4 cup sour cream

6 apples, peeled and sliced

1/2 cup flour

1/2 stick butter

pastry for a 1-crust pie.

Preheat the oven to 425 degrees.

Mix sugar with 1/4 cup brown sugar, 2 tablespoons flour, spices, lemon juice and sour cream. Mix in the apples.

Fit the crust into a 9 inch pie pan. Put the apple mixture in.

Mix the half cup flour with the remaining brown sugar and cut in the butter until the mixture is crumbly.

Sprinkle over the pie. Bake on the bottom shelf of the oven for 10 minutes, then turn heat down to 350 and bake another 35 to 40 minutes.

A filmmaker called last week, asking for memories of the seminal restaurant, Food, which was started in 1971 by a group of artists in what was not quite yet Soho. When I was writing Mmmmm I was also baking desserts for the restaurant. But we were too poor to go out to eat, and I never actually ate there.

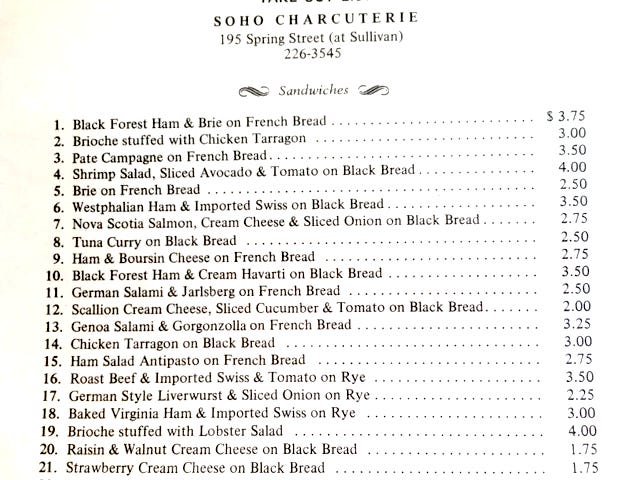

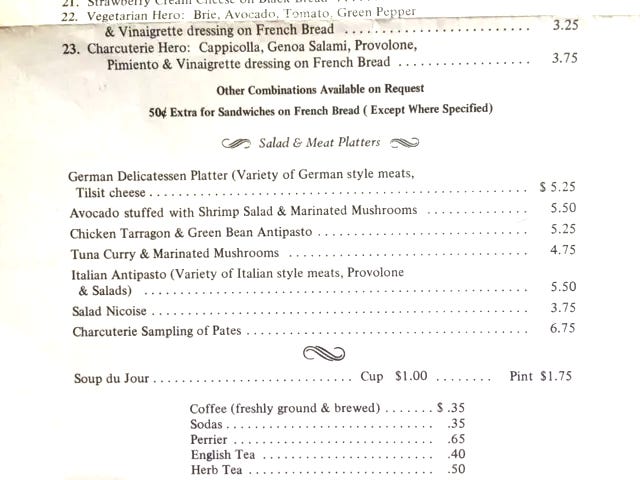

I longed to eat at the Soho Charcuterie too but I couldn’t afford that either. Now, looking at this menu from 1976, I’m a bit stunned; at the time I thought it was an unimaginably expensive restaurant

If Sky Pavillion had been around in the early seventies I would have been SO happy. Back then, on the few occasions when we went out to eat, we would have landed in places like this: a bright, barebones spot on a brash block of New York where you do not expect to find a Michelin-starred chef, Zhongqing Wang, striding into the dining room to discuss the food.

The menu is one of those cluttered folded paper menus tucked into your takeout delivery bag … until you start to read it. Exquisite duck heads! Spicy rabbit! Tofu with crab roe. Mao Xue Wang with its tripe, duck blood and fierce heat.

The night I was there the customers were all Chinese, our waitress spoke only a few words of English, and the chef worried that the heat would be too much. The cold tripe above was indeed hot: I loved it.

A note to all those who joined our special substack-subscriber event last night. Your questions were terrific and it made me very happy to come together as a virtual community.

If you didn’t have a chance to join us live, you can watch a replay of the film and conversation through October 17. Go to https://kinema.com/events/food-and-country-9e2i-a to register and watch.

If you bought a ticket for the live event just email hello@kinema.com and give them the email for your Kinema account and ask for a pass for the replay.

And starting on October 22 you’ll be able to rent the film via Amazon or iTunes.

“(I should probably note that the book was definitely not a bestseller!)”

I bought it when it came out and still have it, stained, torn and taped together.

Thanks for still writing for us.

Your father was a book designer?

I never knew that about you!

PS: The tone of that article is...really patronizing, isn't it?