A Visit to Mexico City

Fantastic food. The world's largest wholesale food market. A vintage menu. A great Mexican gift.

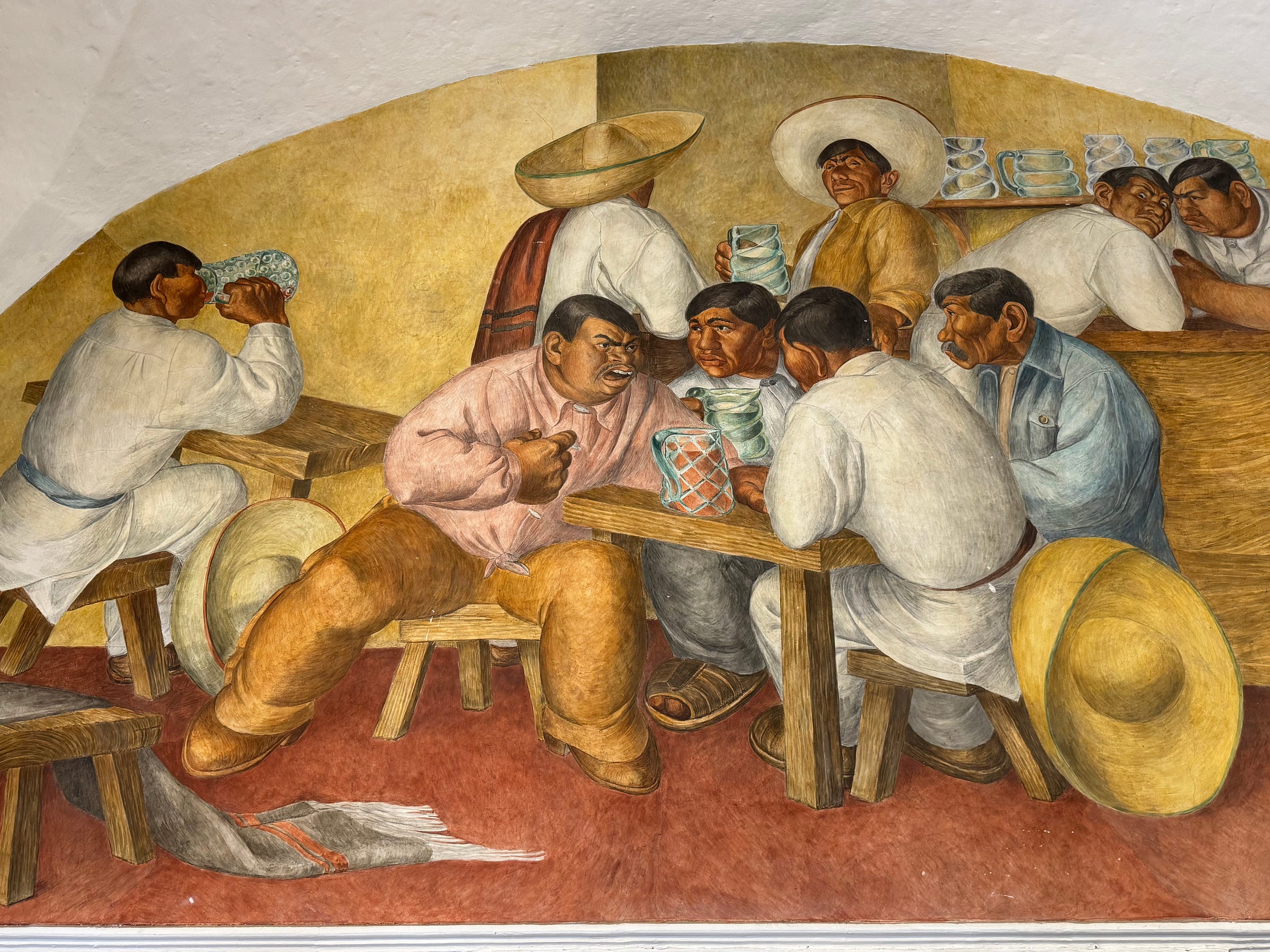

This wonderful mural by Pedro Martinez is in the courtyard of Bellas Artes in San Miguel de Allende. The Martinez murals were one of the highlights of my visit there - they’re not nearly as well-known as they deserve to be - and they got me thinking about the visit I made to Mexico City ten years ago.

Although I’ve spent a fair amount of time in Mexico, I’d never been to Mexico City before. That city - and its food - were a rolling revelation: every day I discovered something new.

September 2015

Why is this person I've never met before kissing me?

Because that is how people greet each other in Mexico. One kiss, on the left check, even if you're just being introduced. It took me a while to stop holding out my hand, American-style, or keep myself from turning my head for the two-cheek European kiss.

It's emblematic of this country: not an air kiss, but a warm one, usually accompanied by a hug. This is a big-hearted, energetic nation which comes as a shock to anyone whose first thought when they hear the word Mexico is “danger!"

The capital is a strange place of enormous contrasts; very rich, very poor and very large. There are 19 million cars here, and the traffic is not bad, it's insane. People think nothing of a two hour ride to get from one place to another. "It gives us more time to eat!" said one friend, scooping up a taco from the stand just outside our idling taxi.

And the food! I've had so many memorable meals here. Here are a few highlights.

The sea urchin (from Baja California) at the wonderful Merotoro, a restaurant so open to the green park outside you feel as if you're eating al fresco. I also fell in love with their octopus-chorizo tacos.

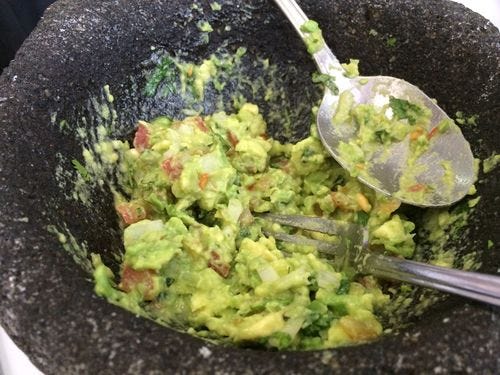

The chiles en nogada at Nico's, a fifty-year old restaurant that was just inducted into the Fifty Best Latin American restaurants. It's one of those places where the waiters know their customers so well they might be family, and people stroll through the restaurant with such casual ease you feel you're all sharing one big table. The food is traditional, and cooked with enormous care and skill. Even something as familiar as guacamole becomes entirely new here.

Had a lovely lunch at Quintonil. Should you be interested, quintonil is an herb, a relative of amaranth, and as far as I can tell none other than goosefoot (also known as lamb's lettuce), my favorite foraged green.

The meal began with nopales ceviche with dried chiles. This was light and refreshing, but what I loved best was the way the chef played with the slightly slimy quality of the cactus paddles. Crisp at first, they dissolved into a completely different texture as you ate. The dried chiles, and that sprinkling of granita, enhanced the effect.

Beautiful sardines with purslane, fennel, seaweed. As delicate as any dish I’ve sampled in Japan, and an entirely new take on Mexican cooking

.

Hiding beneath this adorable little tostada was an oval of crabmeat in a strongly citric sauce. You spooned the sweet seafood onto the crisp tortilla; it was irresistible.

A crisp little tortilla shell filled with chanterelles and other wild mushrooms and glazed in a sweet sauce. But the surprise was escamoles, tender little ant eggs with the texture of marshmallows and a flavor so subtle as to be nonexistent. This was all about texture: a tangle of crisp, soft and chewy that kept your mouth in a constant state of surprise.

Squash blosoms in huitlacoche sauce. It made me think about squash blossoms in an entirely new way.

Duck in recado negro - a kind of mole sauce - with pickled salsify and pureed kohlrabi. A little bit of yang in all this yin.

Escolar - such an appealing fish - with chile guajillo puree and pineapple pico de gallo. No more than a few satisfying bites.

To end the afternoon: a couple of pretty desserts splashed boldly across the plates.

I had come for Mesa Redonda, a conference created by chef Enrique Olvera to discuss the many ways food can can be used as a tool for change. Chef Michel Bras, the poet of the kitchen, discussed terroir in loving detail. Nicola Twilley - a wonderful writer who focuses on the science of food - had fascinating (and provocative) ideas on sustainability. (If you haven’t read her latest book, Frostbite, you should. It’s an utterly fascinating look at refrigeration and the many ways it has changed our world.)

Jorge Larson, a biochemist, talked about biodiversity and Soledad Barutti, a firebrand from Argentina, took on food systems. I think the entire audience fell in love with David Hertz, a Brazilian chef who founded Gastromotiva in the favelas, training the poorest people in the world to be chefs.

My topic was communication (you’ll find it below), followed by Alex Ruiz, the Oaxacan chef, on tradition. Then Lara Gilmore (wife and partner of Massimo Bottura of Osteria Francescana), and Wylie DuFresne discussed creativity in the kitchen.

The talks were short, pithy, and extremely enlightening. It was a wonderful week.

One morning at 4 a.m. we met chef Lalo Garcia of Maximo Bistro for a dizzying tour of the largest wholesale food market in the world, La Central de Abasto. We were lucky to have Lalo to guide us because the market is not only huge, but also so frantically busy that nobody has time to answer questions; this is a far cry from the easygoing public markets of Mexico with their friendly vendors and strolling mariachi bands.

(Lalo himself is an inspirational character; Laura Tillman’s book about him, The Migrant Chef, just won the James Beard Award for literary writing.)

I’d always wanted to visit La Central, and it did not disappoint. But among the many enlightening moments here the biggest surprise was the huitlacoche stand; when I first encountered this delicious corn fungus in the eighties, I was told it was a rare but longed-for trick of nature, much like the botrytis. Now farmers have figured out that all it takes is lots of water to make an ordinary ear of corn turn into the strange creature above.

Talk for Mesa Redonda

I’ve been asked to talk about communication.

I could talk about what food journalism was like when I started writing about food almost 50 years ago. Back then it was considered little more than recipes for an audience of housewives who were thought to be not very bright nor the least bit adventurous.

I could also tell you what it was like to interview chefs back then. Men - they were all men - who’d gone to work at 12 or 13 and spent their entire lives laboring long hours in hot kitchens had very little to say. Their communication skills were mostly nonexistent, and it was difficult to translate their words for the public, to let people know what was taking place in those hidden kitchens. And I could certainly tell you what a joy it was when they were replaced by a generation of smart, articulate and educated chefs who not only wanted to change the face of gastronomy, but also explain exactly why they wanted to do it.

I could tell you what restaurant criticism was like in America in the mid-seventies when I started out. The major newspaper critics were enormously powerful; their words could make or break a restaurant overnight. They were also woefully ignorant of - and generally oblivious to - everything except the cuisines of Europe.

I could talk about what it was like to try and transform the food section of a major newspaper - the Los Angeles Times - when it was considered a cash cow whose entire mission was to bring in enough ads to support “real journalism.” It was a section beholden to the supermarkets and industrial food producers who bought those ads. I could talk about what a struggle it was to be allowed to cover politics, agriculture, health, science and the local food scene in all its complexity. My editors kept saying “Just stick to the recipes little lady,” and the advertisers put up a ferocious fight to make sure that no intelligent writing ever went into the section.

I could talk about the challenge of being an honest restaurant critic, one who felt that my obligation was to my readers, and not to the restaurateurs in the cities I covered.

I could talk about the advent of food television - and its enormous impact on modern food culture.

Or I could talk about the challenges of taking over America’s food bible - Gourmet Magazine- at the turn of the century and rethinking what an epicurean publication might be. About the struggle to cover more than the three r’s - restaurants, recipes and retail. About the enormous pressure not to give people who care about food information that would allow them to make better choices when they shopped.

I’m happy to talk about any that, so if you’re curious, ask me later. Because I don’t have much time, and I don’t want to talk about yesterday. What I want to focus on is today - and tomorrow. I want to talk about the state of the food press today.

It is not, I’m sorry to say, a pretty picture.

In the heyday of food magazines editors asked great writers - not just great food writers - to come up with stories. To think about food in all its wonderful complexity. Meanwhile art directors asked talented artists and photographers to offer us new ways of looking at food. It absolutely stuns me that in a time when everyone is a food photographer, when every cook takes pictures of his dishes and every restaurant-goer whips out a camera, magazines look exactly the same as they used to. Think of the visual possibilities for a magazine with a little imagination! But take a look at any of the main stream food publications and what you will see are shots of food that could have been taken 15 years ago.

There is so much to talk about right now. Here are just a few of the topics I think epicurean magazines should be covering:

Technology and its impact on our food supply. There are some magazines that cover these issues, but they’re in the tech space, not the food space.

Social justice issues: the entire American food system depends on undocumented immigrant laborers who are often exploited.

Food safety.

Tax policy.

Farms and the many problems they are facing.

Food as a weapon.

Important global food products that have an impact on what we eat and how we live. Palm oil comes to mind.

I’m not saying that these topics are not being covered. They are - and far better than they were in the past. As a reader I can find information about all of this, but I have to work hard at it, go to myriad sources in order to get the information I need. If I want stories about social justice, I can go to publications like Mother Jones or Civil Eats. I can get technology information from publications dedicated to that subject like Fast Company. I can get science from the science journals. Newspapers are covering these issues as they never had before, as are mainstream publications from The New Yorker to the Atlantic to Time.

But there was a time - a brief one - when the sort of information cooks need to make smart and informed choices about what they are bringing into their kitchens was offered to them in epicurean magazines. That is no longer the case. What do we get today? Listicals. Gossip. News bites. Nothing too long. Nothing too thought-provoking. Nothing too controversial.

Newspaper food sections have been gutted, and their harried editors are forced to rely on wire copy as they struggle to meet their bosses demands that they tweet on an ever-increasing basis and “communicate” with their readers.

And that’s a problem. In my opinion great journalism does more than merely communicate the information that its readers know they want. The best journalism gives readers information they didn’t know they wanted. And sometimes - often - that means giving people information they’d rather not have. And that is certainly not what is communicated today in the glossy celebrity-driven, focus-group approved mainstream food media.

Let me tell you a story. When I was the editor of Gourmet Magazine I ran a few stories that gave me nightmares, stories that I thought were important but that I also thought might get me fired. One was a story about trans fats, about how Procter and Gamble had known for thirty years that they were dangerous, and employed a group of people whose job it was to contain the bad news. One of our writers, Nina Teicholz, got the retired head of this group to blow the whistle, and he told her how he went to scientific meetings and heckled the researchers who were doing work on trans fats. (You can find that article here.)

My publisher saw the story and said: “Procter and Gamble is one of Conde Nast’s biggest advertisers. What are you going to do when they say they’re going to pull their ads from every Conde Nast publication?”

It was a scary question. And I pretended to be cooler than I felt. I just said, “They wouldn’t be stupid enough to do that. They won’t want to make that much noise. They’ll just be quiet and hope the story goes away before too many people read it.” Which was exactly what happened.

But you know what? The story did get out, and the public decided they didn’t want trans fats in their foods. They didn’t go to the government and demand that they be outlawed. They did something much more effective: they simply stopped buying them.

And that is why communication in the food space is so important. Food is one of the few places where consumers actually wield some power. When people use the power of the purse the big food companies get the message loud and clear.

We see these changes everywhere. Ten years ago people did not know about confinement animal facilities; nobody had communicated that information. Now they do, and we’re seeing enormous changes taking place. Fast food restaurants stopped using battery eggs. Purdue recently bought Niman Ranch and Coleman Meats; they did not do this because they were suddenly sorry that they’ve treated their animals badly. They did this because the public has learned about the horrors of animal confinement facilities and are appalled. It is a direct result of the press giving people information they’d rather not have. People’s food choices matter.

That is why I think it’s so important to communicate this information directly to the people who are buying the groceries and cooking the food.

What we’re seeing now is a food press that has been carved up into little niches. Yes, there are passionate magazines - Lucky Peach, Fool, Cherry Bomb - come to mind. But they are speaking to a small and deeply committed audience when the people we most need to reach are those who have yet to be convinced.

And in today’s world, when so much of our food press has let us down, chefs have stepped into the breach. As chefs have become celebrities, they’ve increasingly used their power to communicate beyond the table. Today, on almost all the fronts I mentioned above, chefs are leading the charge for change. They’ve become great communicators, which is extremely lucky for the rest of us.

The public needs information - and it is our job - all of our job - to see that they get it.

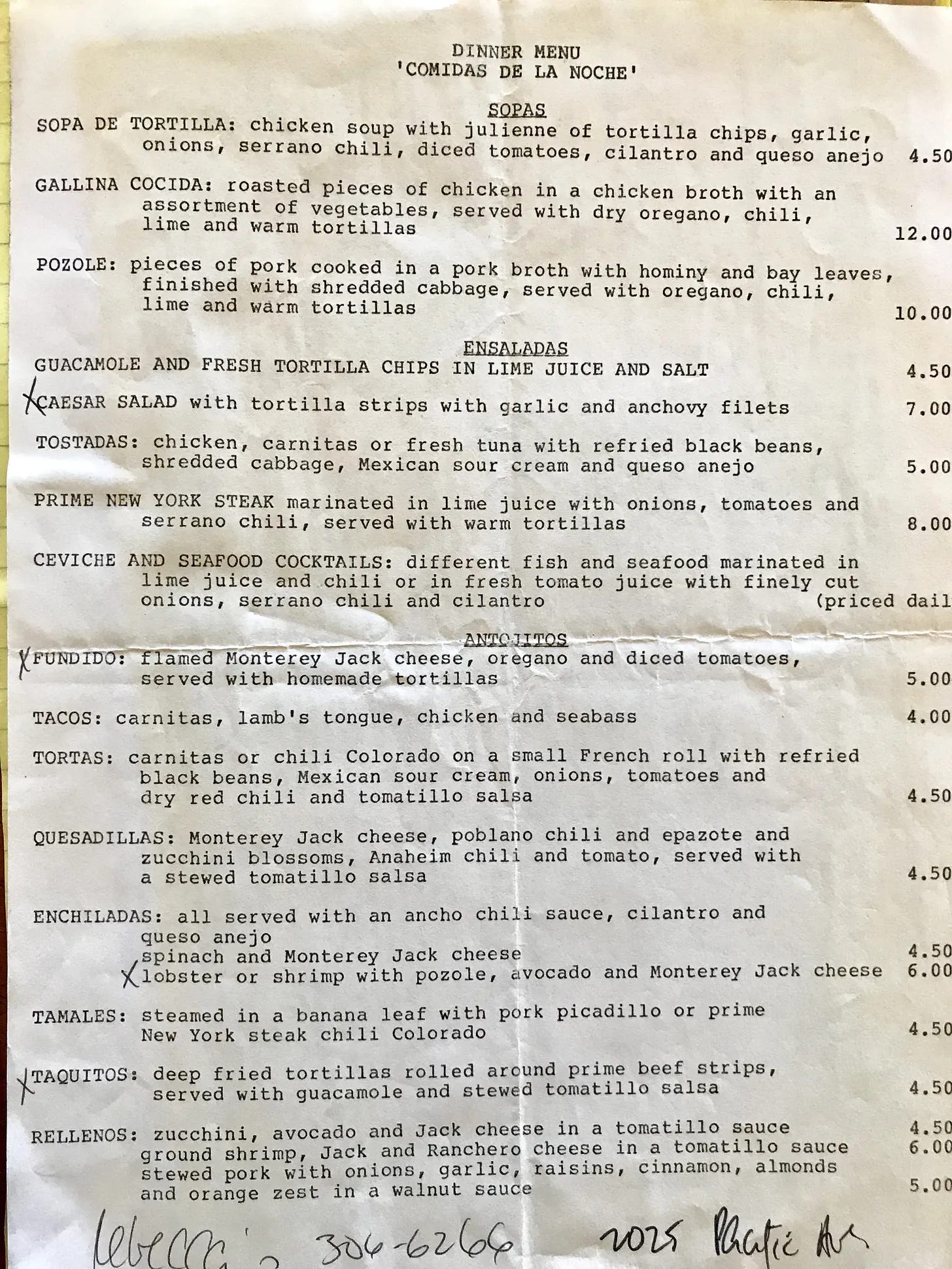

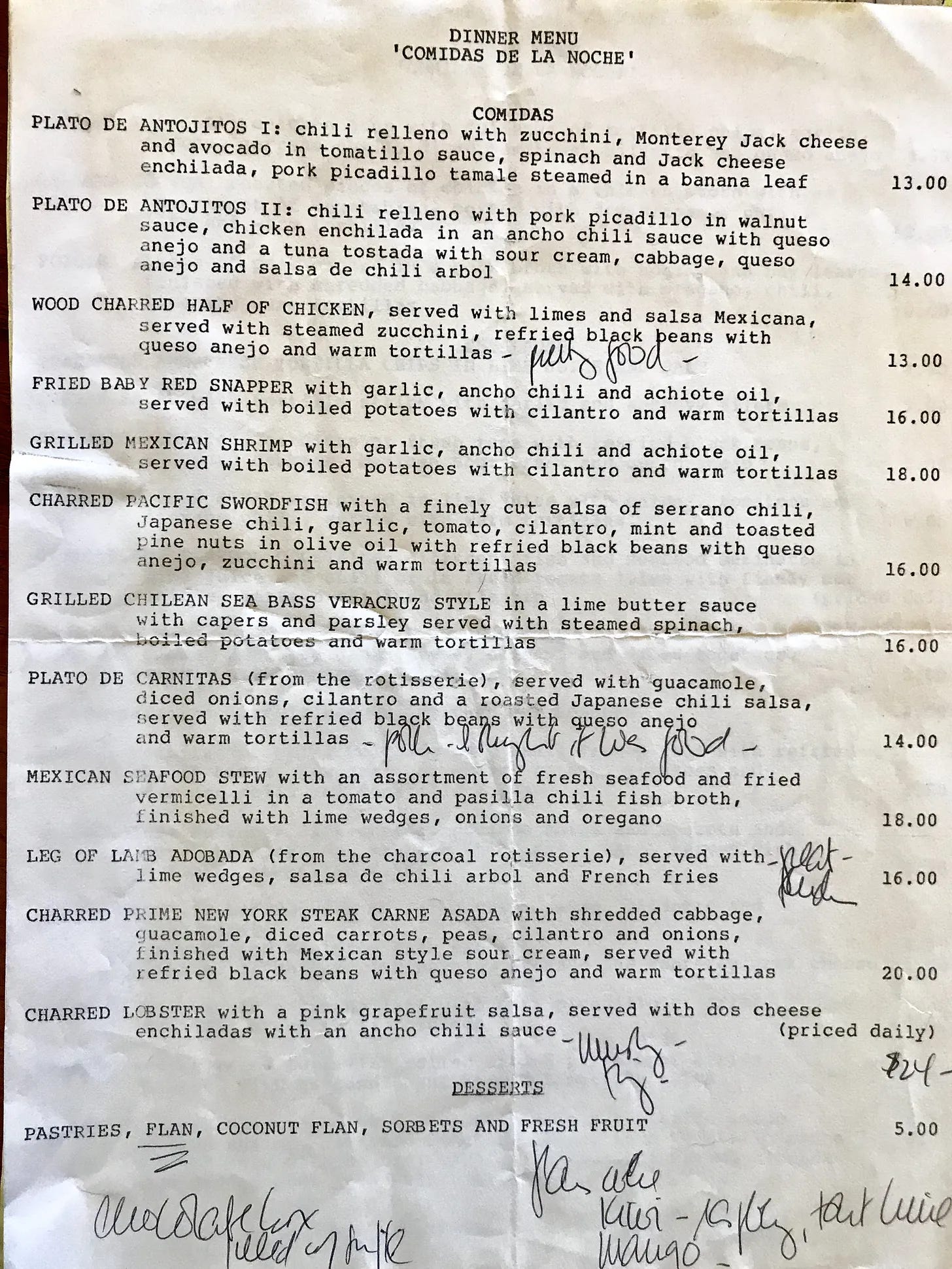

When I think about upscale Mexican food, I often think about Bruce Marder’s Rebecca's, which opened in 1986. At the time Mexican food made with top quality ingredients and served in an upscale environment was not part of the LA dining scene. But Marder loved Mexican food, and in previous restaurants he’d made filet mignon tacos and served them with Chateau Lafite. Now he went big.

Rebecca’s food was part of the draw, but people also went there because Bruce and Rebecca Marder commissioned Frank Gehry to design the interior and he’d created a wild wonderland filled with giant crocodiles, octopuses and rowdy art by local artists.

I bought a lot of gifts in San Miguel, but my favorite may be this salsa picante tea towel from Abrazos, a shop filled with appealing hand-made objects of all sorts. Their entire website is worth browsing.

Thank you for this lovely read. My husband and I visited both Mexico City and San Miguel for the first time last month. We loved both places and have already booked our next trip. Love your work and your excellent journalism. Born and raised in Berkeley.(smile). Appreciate you, Ruth!

Come for the Mexico City memories, stay for that insightful short speech: A whole course in food media in, what, 1200 words? Thank you.